EDITORIAL: The French Hypocrisy

The views expressed herein represent the views of a majority of the members of the Caravel’s Editorial Board and are not reflective of the position of any individual member, the newsroom staff, or Georgetown University.

Demonstrators in Toulouse, France protest against the state emergency and racist, islamophobic, and repressive laws. (Wikimedia Commons)

Brahim Aioussaoi, a 21-year-old Tunisian national, killed three people at a church in Nice on October 30. French President Emmanuel Macron termed the incident an “Islamist terrorist attack.” Two weeks prior, Abdoullakh Anzorov, who had lived in France since age 6, beheaded Samuel Paty, a French middle-school teacher, after Paty showed his class caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad published in the infamous French satirical magazine, Charlie Hebdo. Depicting the Prophet in an image is taboo in Islam; the teacher used the images for a lesson on free speech. Going back just three weeks, two people were stabbed outside Charlie Hebdo’s former headquarters after the magazine republished the cartoons of the Prophet that prompted the deadly 2015 attack.

Macron decided to blame these incidents on “Islamist separatism” while touting that “secularism is the cement of a united France.” However, rather than affirming equal respect for all religions, France’s brand of secularism, known as “laïcité,” has been actively weaponized to combat the so-called “Islamist separatism” that Macron denounced as the “negation of our [France’s] principles, gender equality and human dignity.” By drawing this line, France is not only hypocritical in its application of laïcité by using state neutrality as an excuse to attack the country’s religious minorities—particularly Muslims—but also actively promoting a dangerous policy that will further divide France and fuel radicalization.

In homage to the teacher that was killed, Macron vowed to “hold laïcité up high.” However, in so doing, he holds up France’s hypocrisy even higher for all to see.

Like, What Does It Mean to Be Laïque?

The development of the modern conception of “laïcité”—French secularism—is more recent than many realize, given how ingrained it has become in French society. Similar to the First Amendment in the U.S. Constitution, laïcité governs the separation between Church and State in France by guaranteeing that individuals will be judged equally under the law regardless of their faith. However, with the increase in migration by Muslims from former French colonies to France, as well as the fear of Islam that developed in Western societies following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack, the ideology of secularism has become a framework for controlling the way that religion—particularly Islam—is practiced and manifested in public spaces.

Laïcité originates in a 1905 law that simply defined the separation between Church and State, guaranteeing the right to free religious practice and ending the struggle between the Catholic Church and the secular French state. This definition was later expanded in the constitution of the Fifth Republic, which states that laïcité “assures the equality of all citizens before the law, without distinction to their origin, race, or religion.” This definition nominally continues to hold until the present, with Macron saying in a recent speech that “laïcité in the French Republic” means “the freedom to believe or not believe, the possibility of practicing one’s religion as long as law and order are ensured. Laïcité means the neutrality of the State.”

However, while laïcité promises religious freedom in France, its enforcement (particularly since the 1980s) has been focused on controlling Islam in French society. The term’s corruption in recent political discourse has ultimately resulted in anti-Muslim policies being enshrined in French laws claiming to uphold laïcité while actually discriminating against Muslim people.

From rulings forbidding religious clothing—women, both students and parents, cannot wear hijabs in public schools—to Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin’s recent threat to ban Le Collectif Contre L’Islamophobie en France (“The Collective Against Islamophobia in France”), saying that it works “against the Republic,” the implementation of laïcité in society has been consistently hypocritical.

Speak Softly and Don’t Carry A Big Cross

Rapidly spreading Islamophobia across France has led to antipathy towards immigrants. 57 percent of French citizens feel that there are “too many immigrants” in France, and 67 percent also worry that terrorists are posing as refugees in order to gain entry into the country.

Many French people have taken issue with the fact that a Muslim woman in a headscarf is much more clearly and publicly religious than the average Christian woman—in direct contrast to the privatization of religion popularized by laïcité.

This distrust and dislike of headscarves, and other Muslim religious coverings, first began to rear its head in 2016, when municipal authorities prohibited women from wearing the burkini, a women’s swimsuit designed to provide maximum coverage, on the grounds of protecting laïcité and preventing public disturbances. Similar skepticism exists towards other non-Christian religions.

A mannequin wears the Burkini, a swimsuit designed modesty. (Wikimedia Commons)

When a Catholic nun was told to change her religious attire or face eviction from her retirement home in Vesoul, France, this situation was quickly deemed a mistake and rectified, even prompting the mayor of the town to apologize to the nun—a response in direct contrast to that for the burkini.

This clear hypocrisy reaches its peak in the education system, which is particularly concerning, as it affects impressionable minors. The French government has banned ostentatious religious symbols from being worn inside schools. Although the ruling ostensibly applies to all religions, thousands of Muslim girls could no longer wear their headscarves, while the ruling’s application to Christianity only spoke of crucifixes above a certain size. Such a religious bias teaches children that not only are some religions more acceptable than others but also that how they choose to express their religion could be wrong.

The issue even escalated to the point where non-Muslim French government officials raised an outcry when a student wearing a headscarf was chosen to give a talk to the Parliament about COVID-19. A member of Parliament claimed, during the girl’s speech, that the girl’s headscarf was contrary to French democratic ideals and feminism, and even persuaded several other MPs to leave the meeting in solidarity against the young girl. This institutionalization of religious biases encourages the normalization and proliferation of such harmful actions.

Laïcité Has Had Its Day

Large crosses, like this one in Quito, are not allowed in public in France under laïcité. (Wikimedia Commons)

In many instances, the consequences of laïcité have been dire. As France has codified religious neutrality, it has paradoxically become increasingly hostile to religious minorities, particularly Muslims. After an ISIS-claimed terror attack in which 86 people were killed by a cargo truck in 2016, Nice cracked down on even passing references to Islam. The city even demanded that an investment company remove a sign advertising “Islamic Financing,” which is the practice of conforming to sharia business customs that avoid investment in certain goods and that bar interest charges. Nice’s mayor called the advertisement “a threat to public order” that could inspire “antagonistic gatherings,” apparently finding even the mention of the word “Islam” too controversial to display publicly.

This insistence on assimilation, which has defined French domestic policy through the creation of a cohesive French culture despite regional linguistic differences, alienates both religious and ethnic minorities. France’s inability to confront its own institutionalized racism stunts its race policy: color-blind policy ignores the insidiousness of institutional discrimination. In fact, France has never collected religious demographic information, seeing religious identifiers as a scourge to national unity.

The refusal to acknowledge a problem does not make it disappear. Much of the lack of integration of immigrants and minorities into French culture is propagated internally, codified through protections that classify minorities as immigrants despite the fact that many of these “immigrants” are third- and fourth-generation French citizens. These laws further alienate minorities by implying that their cultural and racial differences are too great to overcome even through complete integration into every facet of French society.

It’s not like France has an improved record on terrorist attacks to show for these actions, either. France has experienced dozens of Islamist attacks in past years, with seven occurring since January alone. Increasingly, these attacks are not the work of organized terror groups but are instead committed by self-radicalized individuals. Online atmospheres exploit the alienation felt by young Muslims—mostly recent immigrants, all men—and instill in them a sense of “us versus them” resentment that culminates in terrorism with the intent to symbolically attack the Western ideals that exclude them.

It’s the Election, Stupid

The incentives for stoking Islamophobia and playing up an almost nationalistic view of laïcité are plain for the many political actors seeking to boost their national profiles in advance of the 2022 French presidential elections. Laïcité is frequently used as an “illiberal legal tool” by most political parties and political actors to question the loyalty of Muslim citizens and advance Islamophobic and xenophobic rhetoric, or, at the very least, appeal to a core base of French citizens who seek out that type of rhetoric. It has the significant ability to mobilize small, but highly active, groups of voters and appeal to the worst fears and basest instincts of many French citizens.

As we head into the 2022 presidential election cycle, with Macron appearing weak and potentially at risk, and with his nationalist rival Marine Le Pen maintaining a substantial base of support, candidates across the spectrum have an incentive to traffic in such xenophobic language and obscure it by invoking laïcité. Macron, as the incumbent, is particularly incentivized to play up nationalism, given his mediocre political performance, falling approval ratings, and his substantial losses in the 2020 municipal and regional elections.

The recent spate of violence, committed by radicalized terrorists—and largely defined by the media as Islamist attacks—presents a critical threat to Macron’s presidency and his chances for re-election. The attacks also give Macron the excuse he needs to engage in Islamophobic rhetoric in order to undercut any public support for far-right candidates by presenting himself as strong against not even terrorism, but Islam.

In early October, Macron publicly denounced “Islamic extremism,” arguing that Islam was a “religion in crisis.” He seemed to be railing against foreign influences supposedly corrupting Islam in France as he unveiled efforts to promote French secularism by strengthening the landmark 1905 law. Unsurprisingly, Muslims in France and around the world were not too happy about the words he used. Macron also doubled down on the need for secularism and complete freedom of expression after Samuel Paty was murdered. The offending cartoons were even projected onto government buildings.

His position is despicable and undermines the true sense not just of laïcité, but of basic democratic principles such as equality between and freedom of religion.

Takes One to Know One

There is no “standard” freedom of expression, no default behavior for everyone to agree upon. Rather, cultural sensitivities have always demarcated—and will always demarcate—the limits of freedom of expression. For one people to impose their standard of freedom of expression on another is nothing more than cultural imperialism. Yet the French political class loves to insist that the French, European “way of life” is inherently superior to those of non-European immigrants, especially those of Muslims.

Railroading over Muslim sensitivities in the name of “freedom” is a self-righteous imposition of values. It’s also a political tool readily available to xenophobes and Islamophobes. Only a year ago, Macron himself noted that “these values of unity and cohesiveness are sometimes distorted and used by those who, seeking to sow hatred and division, use it to fight against this or that religion.” In his recent policy, Macron falls into a trap of his own design.

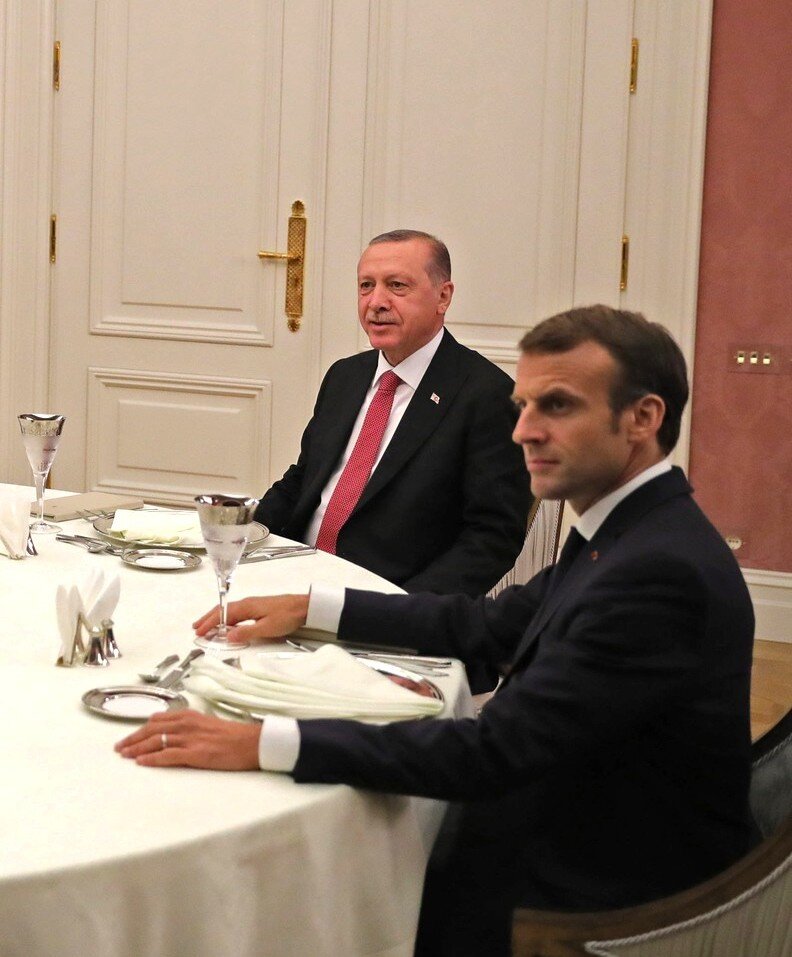

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan rightly called out Macron’s clear bias against Muslims; however, after he went so far as to suggest that Macron had a mental illness, European leaders rallied behind the French President. A spokesperson for German Chancellor Angela Merkel said that Erdogan’s words are “defamatory comments that are completely unacceptable.” The EU’s High Representative, Josep Borrell, echoed that sentiment: “[Erdogan’s words] with regard to the President Emmanuel Macron are unacceptable.”

Macron meets with world leaders, including Turkish President Erdogan, (Wikimedia Commons)

Clearly, European leaders are mad at Erdogan for exercising his freedom of expression, because his words offended them. All the while, they praise Samuel Paty for exercising his freedom of expression, though his actions offended others. They can’t have it both ways.

For a country like France, where leaders and elites exalt—as the Economist put it—“the sacred right to offend,” their hypocrisy is showing.

All of this just goes to show that “universal values” cannot claim to be universal: They’re just the self-righteous impositions of leaders and cultural elites on potentially disparate peoples. It might be more appropriate to call them universal tools by which leaders can wage culture wars.

The way out is as simple as it is radical: recognize that freedom of expression is not, has never been, and can never be a universal, unrestricted, unrestrictable value. We would all be better off assuming we shouldn’t say whatever we want simply because we can. Instead, we ought to recognize the sensitivities that demarcate our individual and collective limits on self-expression. Failing to do this, as the French government has done, only perpetuates an oppressive, arrogant cultural imperialism.

No one “way of life” is the right one. If citizens can understand that, then their leaders will follow.

Have a different opinion? Write a letter to the editor and submit it via this form to be considered for publication on our website!