ANALYSIS: Trends of 2020 – Africa

AFR Editor Kate Fin contributed to this Trends of 2020 piece.

Paulina Song (SFS ‘22) and Kate Fin (SFS ‘21) are the Africa editors of the Caravel. The content and opinions of this piece are theirs and theirs alone. They do not reflect the opinions of the Caravel’s newsroom staff.

From wide-scale political mobilizations in Sudan and Algeria to the spread of foreign power throughout the continent to a continued pattern of encroaching climate disaster, Africa experienced both change and stasis in 2019. Given the major trends of 2019 in Africa, here is what to watch for in the coming year.

The Caravel’s sections are divided along these geographical lines.

Double-Edged Elections

There are 11 presidential elections scheduled for African countries in 2020, as well as a number of parliamentary and regional elections. The past year saw the same number of national elections across the continent, which began in February with Nigeria’s highly contested presidential race. Incumbent Muhammadu Buhari’s victory, though legally contested over minor irregularities in the polls, perpetuated the country’s fledgling democracy, which Buhari’s initial election established in 2015. As Africa’s largest economy and oil producer and the most populous country on the continent, Nigeria’s example at the beginning of the year set an optimistic tone for future elections in African countries with short and rocky experiences with democracy.

Nigerians last went to the polls to elect a president in 2015. (Flickr)

Another of the continent’s most significant economic and cultural powerhouses, South Africa, also held presidential elections in May. Incumbent Cyril Ramaphosa’s election represented a moderate recovery for the African National Congress (ANC), the country’s ruling party since Nelson Mandela’s victory in the 1994 presidential elections. Whereas corruption mired the ANC’s former-leader, President Jacob Zuma, Ramaphosa has led a series of ambitious reforms aimed at restoring the party’s popularity and trustworthiness. Despite recent controversies, Ramaphosa’s reelection suggests that his attempts to restore South Africans’ faith in their democracy may be successful.

Tunisia’s October presidential elections also signaled that the world’s youngest democracy remains committed to progress. Former-academic Kais Saied won a landslide victory in a run-off vote that mobilized a high proportion of young voters.

Unfortunately, not all of the continent’s elections reflected democratic movement. In Mozambique, the elections were hotly contested and included instances of violence and vote-rigging. Malawi’s May presidential elections prompted more than six months of unrest, which saw episodes of violence against civilians and state security forces. The opposition party in Comoros rejected the March presidential election results after violence broke out at multiple polling stations and reports of other voting irregularities emerged.

The continent’s 11 national elections scheduled for 2020 will likely follow this trend of emerging and receding, maintaining and tripping-up democracies. The May presidential elections in Burundi are cause for particular concern, as political upheaval has struck the country since President Pierre Nkurunziza won an unconstitutional third term in 2015. Instances of disappearances, torture, rape, and other intimidation tactics have increased in the run-up to 2020, and the UN has said that “the 2020 elections pose a major risk.”

Burundi's last presidential elections, held in 2015, sparked a crisis which looms large as Burundians prepare to return to the polls in 2020. (Wikimedia Commons)

Extremist violence has rocked the West African countries of Burkina Faso and Mali, which are scheduled to hold National Assembly elections in November and May respectively. This trend may pose significant problems for the elections, as the violence has already displaced hundreds of thousands. Burkina Faso’s prime minister and cabinet resigned in January 2019 over their failure to curb the growing Islamist threat in the country’s North.

On the other hand, many of the elections scheduled for 2020 are expected to be peaceful, free, and fair. Ghana claims to have suppressed a coup attempt in September and will hold presidential and parliamentary elections in December 2020. The country’s democracy, which was established in 1992, is considered strong. Its pattern of reliable democratic transitions has no reason to change.

Somalia is also working toward establishing universal suffrage for its 2020 parliamentary elections. If successful, it will be the first time in 50 years that the country, which currently uses a “clan-based power-sharing model,” conducts “one-person, one-vote” elections. Security remains a critical yet logistically difficult element of the preparations.

Power to the People

Despite the complicated democratic and undemocratic elections that Africa experienced in 2019 (and will likely relive in 2020), two exceptional cases of democratic mobilization took place last year in Sudan and Algeria. Many have referred to these uprisings as “a second Arab Spring,” which could prove infectious for other countries on the continent.

Former-President of Sudan Omar al-Bashir was ousted after 30 years in power in April 2019 after months of protests. These protests began over inflated prices of bread, oil, and other necessities in December 2018. The unrest was met with a violent crackdown by state security forces as protests against economic shortages and inflation morphed into calls for Bashir to step down. As state repression grew more violent, the movement gained more momentum.

Minorities in the country also mobilized, illustrating the widespread dissatisfaction with Bashir’s rule that permeated all regions of the country, including the neglected and heavily repressed Darfur region. Women also played a key role in the movement despite Sudan’s acute gender inequalities. A picture of 22-year-old student Alaa Salah leading protesters in anti-government chants went viral and became a symbol for the new Sudanese revolution.

When the country’s armed forces finally deposed al-Bashir in April, suspending the country’s constitution and calling for a two-year transitional military government, protesters were quick to reject the proposition. After negotiations with movement leaders, a 300-member, all-civilian legislative body was established. In the meantime, al-Bashir’s party, the National Congress Party (NCP) has been banned. The Caravel Editorial Board chose Sudan as its 2019 Country of the Year.

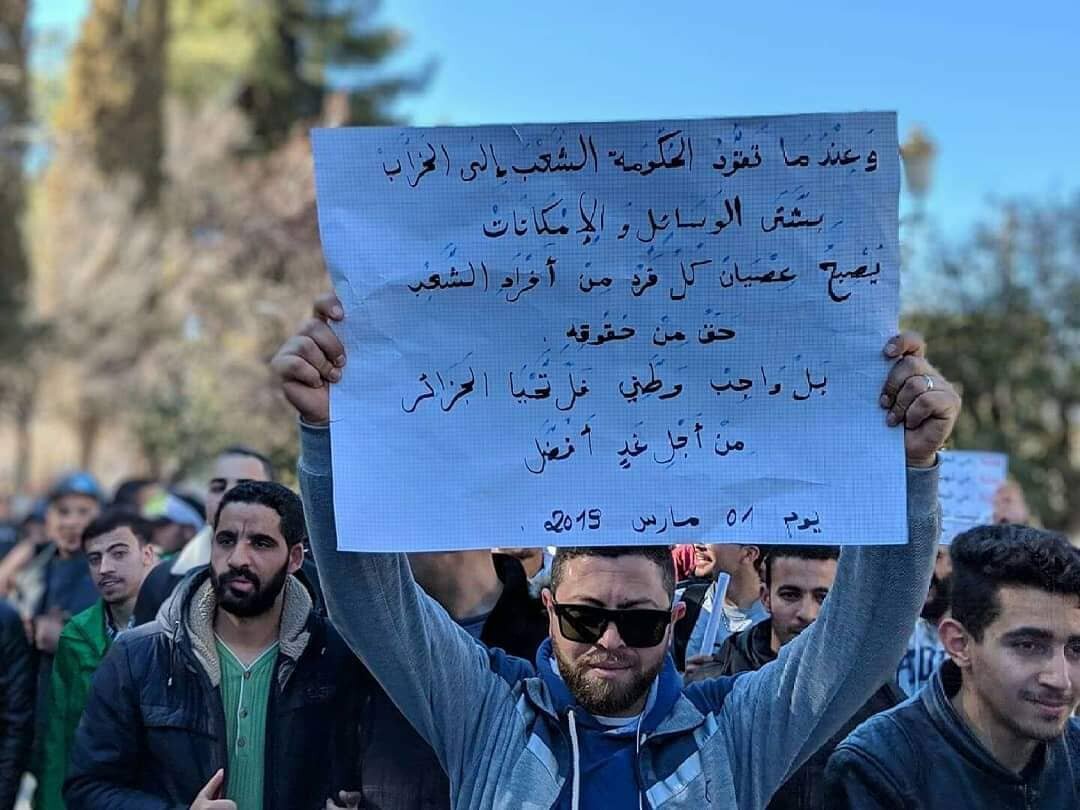

Algerians took to the streets in 2019, culminating in the ouster of the country's president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika. (Wikimedia Commons)

At roughly the same time as Sudan’s movement, protesters in Algeria mobilized in February after former-President Abdelaziz Bouteflika announced his candidacy for a fifth term. The peaceful protests had not been equaled since the Algerian Civil War. Like in Sudan, they persisted even after Bouteflika’s resignation in April. They caused the arrests of numerous leaders close to Bouteflika, including his brother and many leaders of the armed forces. The protests demonstrated Algerians’ frustration with unresponsive and repressive government and their desire for swift, institutional change.

Both the Sudanese and Algerian protesters suffered violence and oppression for their activism. Algerian protesters were arrested and beaten, and the government restricted internet access in key regions. The Sudanese government retaliated by completely disabling internet access in order to prevent media coverage of the state’s violent response to the protests.

These movements demonstrate the increasing willingness of Africans to demand power and a stake in their own government, especially in the face of repressive and unresponsive governments. And, shifting away from previous protest movements on the continent, the protests in Sudan and Algeria were inclusive. Oppressed minorities like Darfur residents and the indigenous Berber took part, and their interests were taken up by the movement at large. Women played a particularly influential role in both countries, as well.

As more African countries move toward democracy, and as Africans grow healthier, wealthier, and better educated, citizens will begin to demand freedom, equality, security, and representation. Tunisia democratized after the Arab Spring in 2011. Algeria and Sudan followed more recently with widespread, peaceful, and inclusive demonstrations against their repressive governments. Perhaps next, Egypt will try its hand at another revolution, as President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi attempts to cling to power for another decade. Experts have already noted how well-suited Africa is to enacting change through nonviolent resistance given its strong history of grassroots anti-colonial movements.

In short, people power will be hard to ignore throughout Africa in 2020.

China & Russia in Africa

The continent has also experienced a surge in foreign interest throughout 2019 that will likely increase in the coming year. While Western powers such as the United States and France have historically maintained significant military presences and economic relations across Africa, the balance of foreign powers in Africa has begun to shift. The U.S. in particular has been looking to scale down involvement in Africa as the Pentagon’s “force optimization” strategy aims to cut troops on the continent by ten percent over the next few years.

By contrast, Russia hosted the first-ever Russia-Africa Summit in Sochi last October. The Russia-Africa Summit resulted in the signing of $12.5 billion in deals in the form of memoranda of understanding. Russian trade with Africa remains relatively small, and the deals signed during the summit may or may not be actualized. However, Russia’s increasing interest in the region signifies its intention to “fuel the perception that it’s a major player,” according to Grant Harris, senior advisor for African Affairs under former-President Barack Obama. Russia’s involvement in the region cannot be dismissed, however, as the country has signed more than 20 bilateral deals on military cooperation with African countries, recently becoming Africa’s largest arms supplier.

Russian President Vladimir Putin met with the president of Benin, Patrice Guillaume Tanon, and many other African leaders at the 2019 Russia-Africa Summit. (Kremlin)

China has also made significant inroads in Africa, from funding the Belt and Road Initiative to founding Confucius Institutes that aim to promote Chinese language and culture. China’s investment and construction in sub-Saharan Africa from 2005 to 2019 total more than $305 billion, making it Africa’s largest bilateral creditor with 20 percent of the continent’s external public debt. China has established at least 54 Confucius Institutes across 33 African countries as of 2018.

Africa has become a new ground for great power rivalries. In 2017, China built a military base in Djibouti just miles from an existing U.S. military base. Former-National Security Advisor John Bolton has also accused Russia of “sell[ing] arms and energy in exchange for votes at the United Nations.”

Whether China and Russia are in the region primarily to challenge Western powers or to take advantage of the large African market, the imprint they have made on the continent is undeniable and only likely to grow in the coming year.

Climate Change

The growing effects of climate change are increasingly alarming on the African continent. Many scientists argue that climate change has contributed to an increase in severe storms and weather conditions, resulting in more than a thousand deaths and hundreds of millions in damages.

In particular, two cyclones caused significant damage in Mozambique and neighboring countries, including Malawi and Zimbabwe, in 2019. Cyclone Idai swept through Mozambique in March as the second deadliest cyclone to make landfall in the Southern Hemisphere. The storm led to severe flooding and a cholera outbreak, with more than a thousand documented cases. Less than six weeks later, Cyclone Kenneth, which evolved from a Category 1 storm to a Category 4 storm by the time it hit Mozambique, became one of the strongest storms on record to make landfall on mainland Africa. Many scientists attribute these unprecedented disasters to climate change, which likely intensified them.

Other parts of Africa have struggled with extreme drought. Forty-five million people across 14 countries struggled with food insecurity in 2019, particularly in southern, eastern, and the Horn of Africa. In Angola, the government declared a state of emergency in three provinces as 2.3 million people were in dire need due to droughts. In Ethiopia, the effects of drought coupled with internal violence and displacement have put 8.3 million people at risk. About 2.5 million people are in need in Kenya, 3.3 million in Malawi, 5.4 million in Somalia, and millions more across Lesotho, Madagascar, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and more.

Economic projections show significant economic risks in the form of lost crops, decreased productivity, and health-related expenditure. If temperature increase is limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, the target for the 2015 Paris Agreement that many scientists believe is no longer achievable, African countries as a whole would expect to see a 3.8 percent decrease in GDP per year beginning from 2100. If global temperatures increase by three degrees Celsius, Africa’s GDP could see as much as an 8.6 percent annual drop after 2100.

The necessity of combating climate change leaves a unique role for many African countries still in the process of building their economies: rather than building an industrial, carbon-heavy economy, countries can shift toward economies built on sustainable, low-carbon, green infrastructure.

Last year, Morocco built the largest concentrated solar farm in the world with the potential to reduce potential carbon emissions by 760,000 tons. The country laid out a goal of generating 42 percent of its power from renewable sources by 2020. As of the latest available data, Morocco was on track to achieve that goal, with 35 percent of its energy coming from renewable sources by July. Similarly, South Africa has sought to reduce emissions by implementing a carbon tax scheme, which came into effect in June. This policy has the potential to reduce the country’s carbon emissions by 33 percent, experts say.

While policies implemented by individual countries to address climate issues may achieve huge gains and set examples for other countries to see, ultimately, cooperation across the continent will be key to tackling climate change. This collective spirit was exhibited in March when more than 3,000 delegates from across Africa convened in Accra, Ghana, for Africa Climate Week.

Topics discussed included mitigation and adaptation techniques, data-sharing on climate change responses, and access to funding to implement solutions.

However, the existence of Africa Climate Week does not mean consensus in any form on the issue of climate change. In November, more than 25 ministers attended the Africa Oil Week conference in Cape Town, South Africa, during which Extinction Rebellion, a climate activist group, staged protests.

Conference organizer Joanna Kotyrba described the conference as “a platform that brings together stakeholders from across the oil and gas value chain to discuss and debate the most important issues facing the sector, including how technology and innovation with deliver energy responsibly for a sustainable future.”

Extinction Rebellion, however, claimed that “the conference organisers have omitted even the faintest reference to climate change in their programme, which is inconceivably irresponsible considering the severity of our ecological situation.” Whatever the true intentions of the conference was, the fact remains that competing interests among other things—electoral fraud, political violence, foreign influence, and more—frustrate cooperation over issues that will determine the future of not only the continent but also the world. In such a high-stakes situation, cooperation is all the more necessary and all the more difficult to achieve.