EDITORIAL: Blood & Soil – Making a Nation

The views expressed herein represent the views of a majority of the members of the Caravel’s Editorial Board and are not reflective of the position of any individual member, the newsroom staff, or Georgetown University.

Citizenship serves as a critical tool to account for, provide for, and classify the people living inside the borders of a country. It ensures access to certain rights and privileges that those without such status cannot gain. In countries around the globe, the regulations regarding citizenship have historically played a huge role in shaping national identity by including or excluding groups from the benefits of belonging.

In light of xenophobia’s global surge in recent years, particularly in countries that tout themselves as international leaders and strong democracies, we must examine the impacts of politicizing citizenship and how easily minority groups in countries can lose their legal status (and, subsequently, their access to benefits such as healthcare or protection under the law). From the United States, the oldest extant democracy, to India, the largest democracy by population, the ease with which governments can weaponize citizenship to serve overtly political motives shows the inherently undemocratic nature of the policies underpinning legal xenophobia today.

Birthright, Bloodright, or Bargaining Chip?

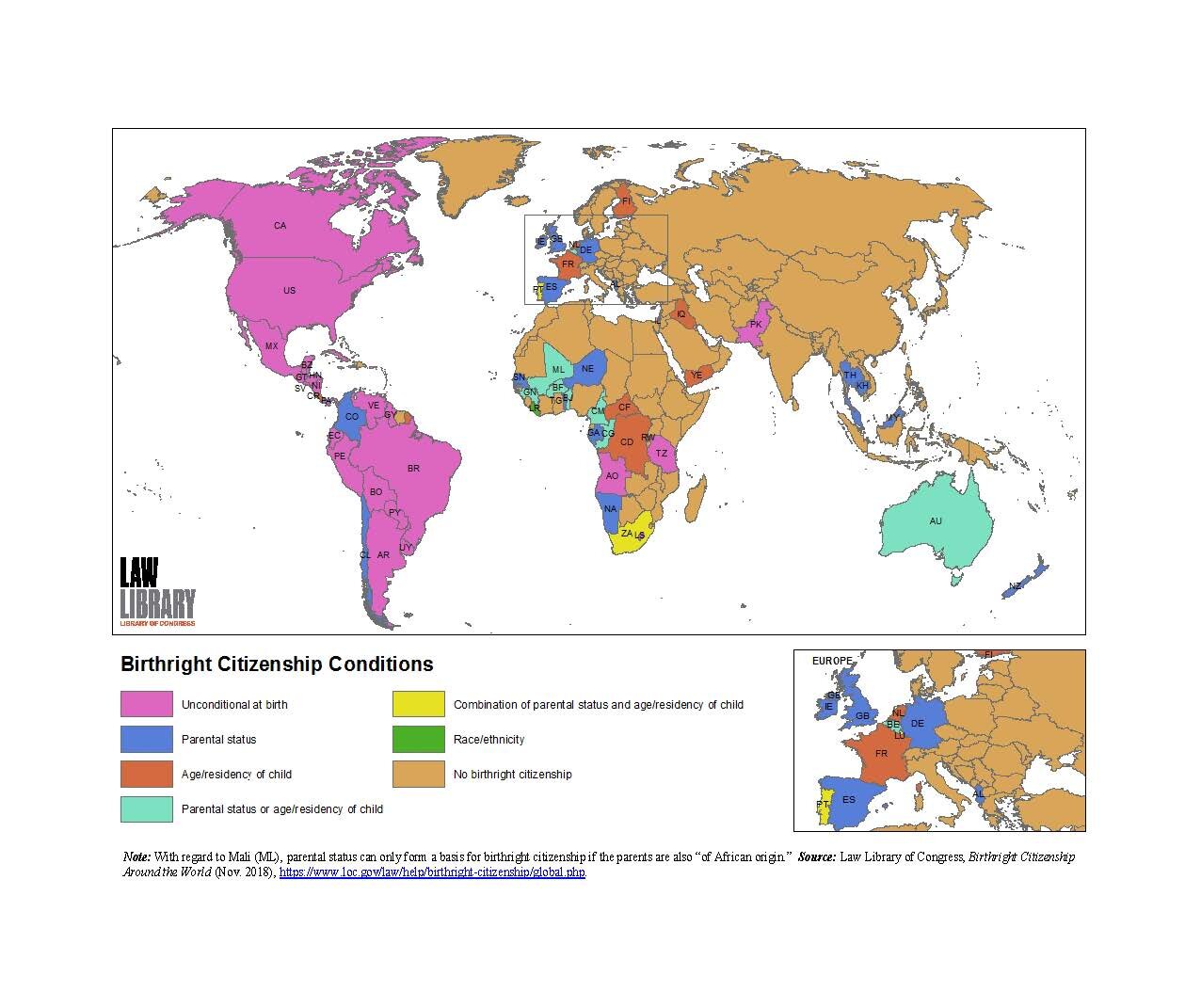

The conditions for granting national citizenship have a contentious history. A long history of jus soli (literally, “right of land”), or birthright citizenship, in which any child born in a geographic territory receives that territory’s citizenship, was supplanted in the 19th century by jus sanguinis, or “right of blood.” This new standard, under which citizenship is given only to those with blood ties to existing citizens, spread across Europe as part of the Napoleonic Code and across the world as part of colonial civil law systems.

Countries are increasingly turning to mixed citizenship regimes. (Library of Congress)

Interestingly, most countries with jus soli citizenship laws today are in the Western Hemisphere. International Monetary Fund (IMF) data shows that, on average, jus soli countries have income per capita about 80 percent higher than jus sanguinis ones. Birthright citizenship can create a sense of security for those (often vulnerable) non-citizen residents who would be excluded by jus sanguinis. In doing so, it creates the conditions for economic development and social inclusion. The IMF found that exclusive citizenship regimes can create labor market distortions, damage public sector efficiency, and shorten investment time horizons. In fact, according to the data, countries that switched to jus sanguinis citizenship after independence from their colonizers had income about 46 percent lower than projected under a continuation of jus soli.

Exclusive citizenship regimes can be a weapon that governments wield to punish ideological enemies and ethnic minorities and reward allies and ethnic majorities. Citizenship confers benefits, and a denial of citizenship imposes costs—social, economic, and political—on targeted individuals or groups. Citizenship can also be a tool of foreign policy, whereby states justify intervention abroad through a need to protect their citizens in other places. Misuse of citizenship law for domestic or foreign political goals harms vulnerable populations and undercuts the potential for inclusive economic growth.

Tyranny of the Majority

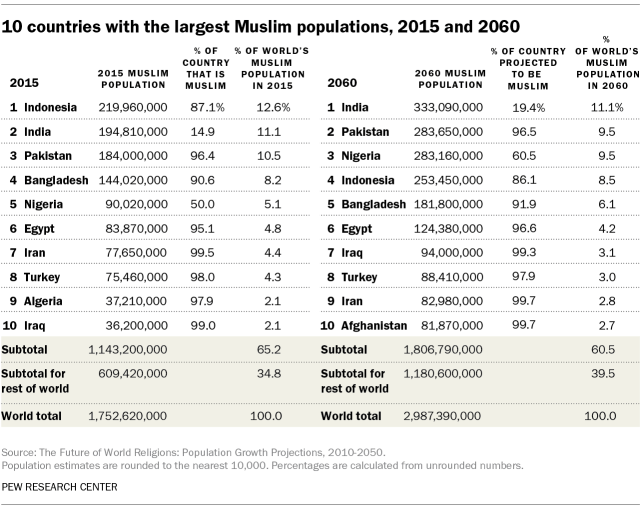

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist agenda has resulted in a series of egregious political attacks against the country’s Muslim population using citizenship law. Beginning in August 2019, the government revoked the autonomous status of Jammu and Kashmir, India’s only Muslim-majority state, and detained thousands of citizens and local leaders.

At the end of that month, the government released the final National Register of Citizens (NRC) for the state of Assam, home to India’s second-largest Muslim population behind Kashmir. The NRC is an official list of legal citizens. All 33 million residents of Assam were required to provide proof that they or an ancestor lived in Assam before March 25, 1971. The NRC effectively revoked the citizenship status of around two million people, mostly Muslim, who were unable to produce the necessary documents, such as property deeds or birth certificates. They have 120 days to file an appeal before the Foreigners’ Tribunals can claim the right to detain all “illegal aliens” and deport them to their “native countries.” The government is currently debating implementing a nationwide NRC.

Modi’s government further pursued measures to discriminate against Muslims through passing the Citizenship Amendment Act on December 11, 2019. The act provides a fast-track to Indian citizenship for migrants from the Muslim-majority countries of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh if they identify with one of six religions: Hindu, Christian, Buddhist, Sikh, Parsi, or Jain. Notably missing from that list are Muslims. Thousands took to the streets in response to the Citizenship Amendment Act, prompting the government to mobilize soldiers, shut down the internet, and target protesters using facial recognition systems in conjunction with its biometric database, the largest in the world. In the first ten days of protests, more than 1,500 people were arrested. Controversy over the citizenship law also triggered violence against Muslims, killing more than 40 and injuring 200. Human rights organizations have denounced the violence as pogroms, with videos showing the Delhi police condoning and at times facilitating the violence.

On March 3, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights made a rare decision to challenge the citizenship law in India’s Supreme Court. India’s Foreign Ministry has requested that the petition be overturned. For a country that prides itself on being the “world’s largest secular democracy,” India’s recent citizenship legislation marks the country as anything but secular and democratic. Though India’s government continues to deny any bias against Muslims, such blatant discrimination and attempts to disenfranchise the country’s Muslim population provides a crucial reminder that citizenship is just one legislative decision away from being redefined or revoked.

Ex Post Facto Xenophobia

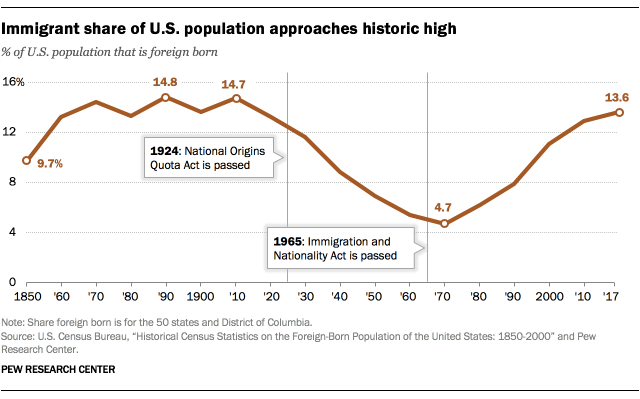

The United States has always held the status of citizenship as a political issue, legislating who is and is not eligible. However, the conversation throughout the Trump administration has increasingly shifted from asking, “Who can gain American citizenship?” to “Who can lose American citizenship?” The Justice Department’s February 26 announcement that it would dedicate a group of employees to reviewing denaturalization cases most clearly demonstrates the shift, falling in line with the administration’s broader goal of investigating immigrants who potentially obtained their citizenship through illegal means.

While the head of the Justice Department’s Civil Division, Joseph Hunt, said in a statement that “the Denaturalization Section will further the Department's efforts to pursue those who unlawfully obtained citizenship status and ensure that they are held accountable for their fraudulent conduct,” the so-called ‘fraudulent’ cases require a very low burden of proof for prosecutors. This leaves a significant number of immigrants who have already obtained their green cards vulnerable to losing their status due to issues such as a lack of correct adoption papers, a misspelled Anglicized name, or a case of stolen identity. In 2008, an Obama administration rule began the pursuit of immigrants with criminal records. But, 40 percent of all civil denaturalization cases since filed by the Justice Department were filed after 2017, indicating an overall increase in the law’s use as a tool to remove citizenship. Over the past three years, denaturalization cases referred to the Civil Division have increased by 600 percent.

Critics of the new task force express worry that the policy displays a broader and more troubling idea in the United States that naturalized citizens have fewer rights and that successfully naturalized citizens should not assume that they are safe in the country. The new civil process of denaturalization offers citizens neither access to a public defender nor a statute of limitations, further creating a hostile environment toward immigrants in the U.S., whether or not they have obtained citizenship. While the task force claims that it will focus primarily on serious violations of the law, that vague statement creates an uneasy grey area for naturalized citizens, who can never be sure when someone will come knocking at their door.

Blaming Victims in Taiwan

The restrictiveness of Taiwan’s nationality law has left thousands of people stateless, with a United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) spokesperson saying, “this limbo is a tragedy.” The law requires foreigners that marry a Taiwanese citizen to renounce their foreign citizenship before being naturalized. Hundreds, if not thousands, of Vietnamese women tricked into marriage in Taiwan to escape poverty have found themselves stateless after being abandoned, divorced, or widowed by their husbands after renouncing their original nationalities. Without citizenship, they lose access to government services like healthcare and state schools for their children.

Expatriates receive national identification cards under a 2016 law change that allows dual citizenship for talented longtime residents who have served the arts, science, or business in Taiwan. (Republic of China Department of the Interior)

An overhauled nationality law promulgated in 2016 aimed to redress some of the concerns raised by the UNHCR, but it falls far short, only making exceptions for domestic violence victims and disqualifying stateless divorcees or widows who remarry from citizenship. The law also revokes the citizenship of Taiwanese citizens who marry foreign nationals and those who acquire foreign citizenships in countries that allow for dual citizenship, even going so far as to strip citizenship from the unmarried children of such persons. Using citizenship as a restrictive covenant pushes people to the fringe of Taiwanese society and undercuts the country’s promise to be a voice for pluralism, democracy, and inclusion in East Asia.

Putin’s List

In 2008, Russia invaded the bordering Georgian provinces of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Russia recognizes South Ossetia and Abkhazia as independent states and maintains de facto control over the two territories; Georgia claims sovereignty over both. Russia justified its invasion on the grounds that it was protecting Russian citizens.

Russia has taken military action allegedly on behalf of ethnic Russian populations in Georgia and Ukraine. (Twitter)

Technically, that claim is correct. In the early 2000s, Russia issued passports en masse to Georgian residents of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. So, when Georgia attempted to reassert control over its breakaway provinces in 2008, Russia invaded. After all, it had to protect its “Russian citizens.” The process, known as “passportization,” cleverly subverts international law to grant Russia an ostensibly legal way to pursue its geopolitical objectives. Russia repeated the process in Ukraine and Crimea, where “ethnic Russians” gave President Vladimir Putin an added justification for the annexation of Crimea and the invasion of eastern Ukraine. Russia’s weaponization of citizenship exposes the idea as nothing more than a title conferred by the state, a ready legal pretext for aggressive pursuit of state interests.

Rewriting the Social Contract

A state is not a state without its citizens. A government needs a unified group of people that it can claim to rule over and be ruled by. But, when governments limit who count as citizens, rulers cement their control: a limited citizenry creates and empowers a limited set of rulers.

Modi can ensure that Indian Muslims lose political power in states like Assam; Trump can shrug off long-standing U.S. residents as aliens needing deportation; Taiwan’s government can judge who deserves necessary public services. Rulers can expand the definition of citizenship, too, and, by claiming they rule over more people than they actually do, use it to prosecute claims against other states like Russia has against both Georgia and Ukraine.

To say that the idea of citizenship is merely a tool of rulers, however, obscures the fact that citizenship helps those who hold it. There exists a social contract between government and citizen: a person’s citizenship theoretically grants them the rights and services promised to them by the rulers of that state. In an ideal world, they can choose those rulers, they can own property, they can move more freely with their passport, they can receive a fair trial, and they can get free public goods like healthcare and infrastructure.

The benefits of citizenship to citizens are real; however, governments’ exclusive abilities to bestow it allows for discrimination in who gets those benefits. The challenge, then, lies in choosing leaders who can promise those benefits without prejudice, cultivating a citizenry that is unafraid to expand itself, and creating a society that welcomes all with open arms while being honest about what it can provide to its members.

Have a different opinion? Write a letter to the editor and submit it via this form to be considered for publication on our website!