Special Report: The World Wide Web of Repression

The Baitur Rahman mosque in Silver Spring, Maryland serves as the national headquarters of Ahmadiyya Muslim Community USA. (Courtesy of Harris Zafar)

Amjad Mahmood Khan and Harris Zafar woke up on December 24, 2020, to a strongly worded email from the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA). The message demanded that they take down their website, trueislam.com, within 24 hours—or face legal and financial penalties.

Khan and Zafar are U.S. citizens living in the United States; Pakistan’s warnings do not threaten them directly. But Khan and Zafar do happen to be leaders of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community in the U.S. Together, the two manage the external affairs of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community USA: Khan as its National Director of Public Affairs and Zafar, who works under Khan, as its National Spokesperson.

The government of Pakistan, however, would prefer they drop the word “Muslim.” Under Pakistani law, Ahmadis cannot claim to be Muslim. Ahmadis in Pakistan can be persecuted and politically targeted unless they renounce their claim to being Muslim, and they cannot even publicly worship at their own mosques or publish the Quran in print.

To help Pakistani Ahmadis practice their own religion, Ahmadiyya leaders abroad developed an app that allowed their fellow Ahmadis to read an annotated copy of the Quran at home.

The PTA wouldn’t have that, either. On December 25, the PTA sent Google a legal notice asking them to take down an “unauthentic version of Holy Quran uploaded by Ahmadiyya Community [sic] on Google Play Store” in order “to remove the sacrilegious content.”

Not two days later, Google removed that Ahmadiyya-made Quran app from the Play Store in Pakistan. Just last month, Pakistan blocked trueislam.com within its borders, too.

By preventing Ahmadis in Pakistan from accessing community resources and a copy of the Quran, Google is enabling the Pakistani government to continue its repression of the Ahmadiyya Muslim community within and outside Pakistani borders.

The Caravel sat down with both Khan and Zafar to discuss Pakistan’s latest moves against their community. Pakistan’s action was not unexpected: Khan and Zafar have always known the Pakistani government would take steps to restrict Ahmadis. It was Google’s quick capitulation that surprised them.

Anti-Muslim Muslim Club

The PTA’s December 24 email to Khan and Zafar minces no words:

“It has come to the notice of Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (“PTA/Authority”) that your Social Media Website i.e https://trueislam.com, is involved in hosting/dissemination of content related to Ahmadiyya/Qadiani’s [sic] Community who are claiming themselves to be Muslims. It may be noted that Ahmadiyya/Qadiani’s can neither directly/indirectly pose themselves as Muslims nor call or refer to their faith as Islam.”

Due to a difference in their notion of prophethood, Ahmadiyya Muslims are distinct from their Sunni and Shi’a counterparts. Ahmadiyya Muslims consider Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, a colonial-era Muslim thinker and public intellectual in Indian Punjab, both a prophet and the promised messiah. After Ahmad died in 1908, his followers established their own caliphate and elected a khalifa (caliph). Most Muslims consider Muhammad the final prophet and do not recognize Ahmad.

The Masjid Aqsa in Qadian, India, where Mirza Ghulam Ahmad founded the Ahmadiyya Muslim community. (Wikimedia Commons)

The Ahmadiyya sect has since spread around the world to Africa, Europe, and North America, but Pakistan is home to the largest Ahmadiyya community. Pakistan is also the only majority-Muslim country to exclude Ahmadis from the label “Muslim.”

The Pakistani constitution of 1973 was amended in 1974 to clarify, very specifically, that Ahmadis are not Muslim and may not call themselves Muslim. The roughly four million Ahmadis in Pakistan cannot call their houses of worship mosques or make the call to prayer; cannot greet others with “as-salamu alaykum,” the traditional Muslim greeting that means “peace be upon you;” cannot publish; and cannot get a passport or hold a government job without either registering as non-Muslim or denouncing their sect’s founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, whom they consider a prophet. To break any of these rules is blasphemy—the legal punishment for blasphemy is death.

By catering to the Ahmadi Muslim community, the trueislam.com website and the Ahmadi-made Quran app both violate the laws of the Pakistani Constitution and Penal Code.

Now, a revamped set of blasphemy laws—the 2016 Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act and its November 2020 amendment—allows the Pakistani government to press charges against this sect of Islam in cyberspace, even abroad. The laws apply to “any act committed outside Pakistan by any person if the act constitutes an offense under [these laws] and affects a person, property, information system or data located in Pakistan.”

Because Khan and Zafar refused to comply with the PTA’s request, the PTA has leveled charges and threatened a fine against them—again, despite the fact that the two are U.S. citizens.

Zafar told the Caravel that he and Khan aren’t the only ones Pakistan is targeting: “We currently have members of our community… who have arrest warrants out for them, and it's because they did something like providing their voice for an audiobook that's out on our website, or making a comment on a YouTube video. But now it's considered a crime because you're doing something that's promoting the Ahmadiyya community or representing our community, even in the cyber world.”

Pakistan’s government is “becoming more and more aware of the digital content that the Ahmadiyya community has,” said Zafar. “With this new law from November, that just empowers them to basically govern [sic] Pakistani law in the cyberspace.”

Playing God

The new blasphemy rules will change the Pakistani internet. Reuters summarizes them: “Any platform that has more than half a million users in the country will have to register with the PTA within nine months and establish a permanent office and database servers in Pakistan within 18 months.” Service providers and social media companies are legally obligated to localize Pakistani data on servers within the country and to turn over that data to the government upon request.

The rules empower the PTA to remove or block digital content that allegedly threatens Pakistani national security, and they give the PTA leeway to fine service providers and social media companies more than $3 million for non-compliance with takedown orders. The PTA could even choose to block whole companies.

These new laws are a big change. “It’s kind of a power play to force tech companies to make it [Pakistan’s] data,” said Zafar. “Once it is, then [Pakistan can] enforce more rules on what they’re allowed to do with our data.”

Hence the emails to Zafar and Khan and the injunction against Google: if Google continued to host the app and website in Pakistan, the “PTA shall be constrained to initiate further action under the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act 2016 (#PECA) and Rules 2020.”

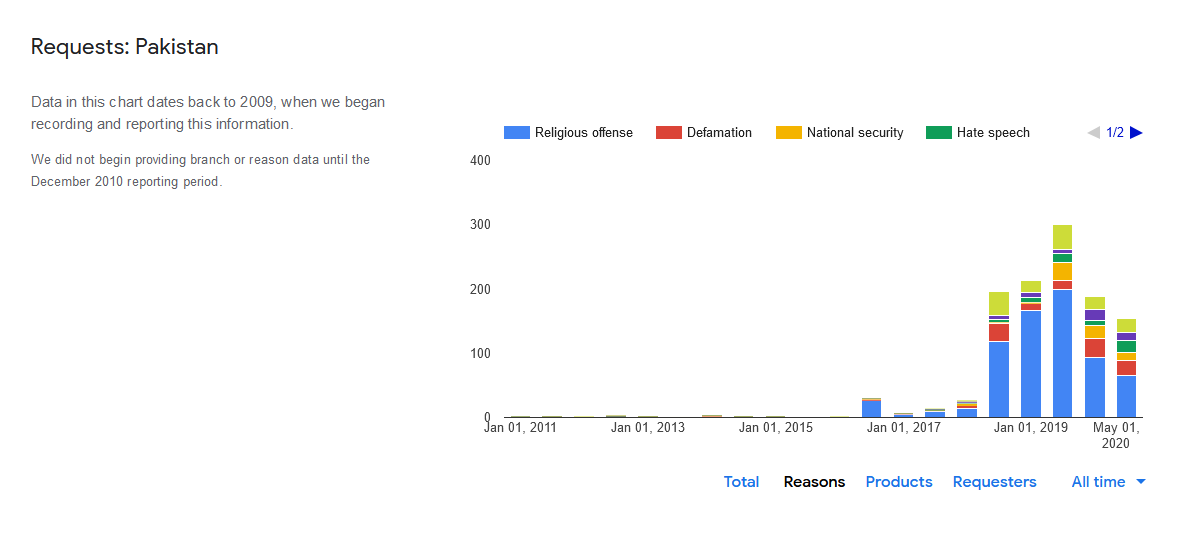

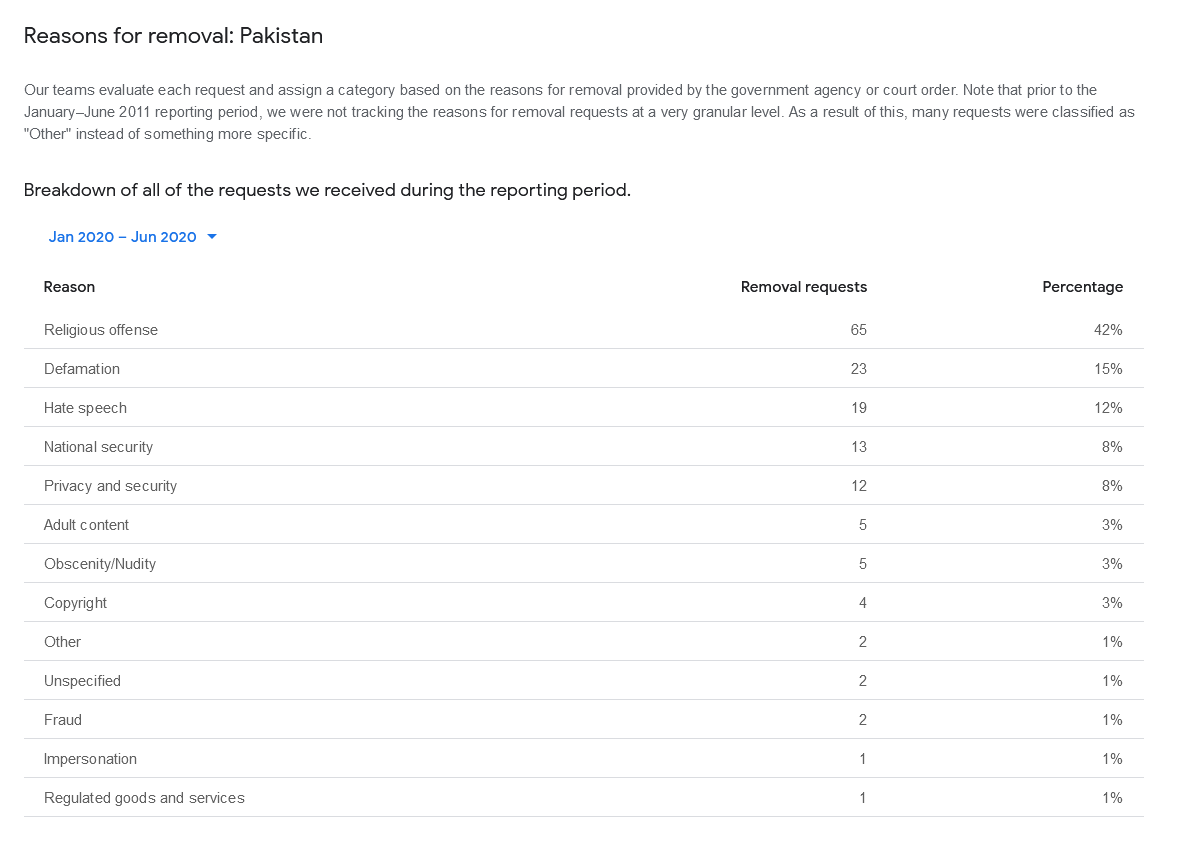

Despite pressure from governments like Pakistan’s, Google has promised not to remove content on a whim. In an effort to be transparent, Google keeps track of every government agency’s or court’s request for data removal that it receives: “We review these requests closely to determine if content should be removed because it violates a law or our product policies.” Yet its takedown guidelines say nothing about a commitment to free expression or free worship.

When the PTA asked Google to take down the Ahmadiyya Quran app, citing their many blasphemy laws, Google complied within just two days. The company explained the takedown as such: “We initially asked for more information on the applicability of the cited provisions of law and the decisions of the court order to the app. Upon further review, we locally blocked the app from the Google Play Store in Pakistan.” All they admitted was that the app had violated Pakistan’s repressive blasphemy laws.

Google recognizes Ahmadi Muslims as a minority group but appears to accept the existence of Pakistan’s repressive blasphemy laws at face value. (Google Transparency Report)

“Google touts compliance with global human rights standards,” said Khan. “But that's mere lip service. It's not as if they can't resist the PTA's orders; they have in other cases, but just don't want to do so in this case.”

Indeed, a survey of what Google chooses or refuses to take down in Pakistan lends Khan’s accusation some credence.

The PTA asked Google to take down a Google Drive file “containing the content of an open letter from concerned faculty members across several universities in Pakistan regarding academic freedom and increased repression on university campuses.” Google let it stay.

The PTA later asked Google “to remove 6 apps on Google Play containing content related to the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement. The [PTA] cited hate speech and unlawful online content as the legal basis for removal.” The Pashtun Tahafuz Movement, says Brookings, is “a non-violent protest movement demanding rights for Pashtuns” in Pakistan that is agitating for representation—a stance that the government categorizes as hate speech. Google let that stay, too.

Both takedown requests, made before Pakistan updated the blasphemy laws, concerned questions of free expression. Under Pakistan’s new laws, Google’s refusal to comply with the PTA’s takedown requests could have incurred suspension of services and a court-ordered fine.

“Moral courage,” argued Khan, “means fighting against the tide of cruel religious repression, even if that means risking short-term commercial harm.” In 2020, Google earned nearly $200 billion in revenue. Pakistan’s $3 million noncompliance fine is but pennies compared to that. It’s not clear that Google can’t afford to pay.

Hypothetically, if Google did refuse to pay the fine, Pakistan could shut down Google’s operations in the country.

But is it worth denying 220 million Pakistani citizens one of the internet’s most important services simply to deprive a religious minority group of a Quran they could read on their phones?

Given how the Pakistani government couldn’t even ban Tiktok, Khan isn’t convinced that banning Google would work at all: “TikTok was down in Pakistan for three days. Everyone on the streets were [sic] angry and [TikTok] was reinstated.” If that’s how Pakistanis reacted when TikTok was challenged, Khan seems to be arguing, then imagine what they might do if Google were banned.

Despite the fact that Google should know that its importance to everyday people probably deters Pakistan from shutting it down, “We definitely see Google kind of acquiescing and surrendering to any demand,” according to Zafar.

Khan isn’t really sure why Google was so ready to take down specifically Ahmadi apps in Pakistan. “Google may be horse trading other concessions with PTA in exchange for our issue,” he guessed. “In other words, we're kind of like a wedge issue for Google, and we're effectively a leverage point for them to agree to not reinstate our content in exchange for extracting benefits from PTA that would be more commercially beneficial for them in the future.”

Google Hangouts

“This is not the first app that Google has taken down at the request of the Pakistan [sic] government,” said Zafar. He told the Caravel that the Ahmadiyya community put out its very first Quran app, a basic pdf scan of the holy book, in 2016.

In September 2018, Google notified the Ahmadiyya developers that the PTA had sent them a takedown notice. Google initially planned to comply, but the company reversed course and engaged with the Ahmadiyya community instead. In March 2019, Google met with Ahmadiyya leaders in the U.S. Buzzfeed reported that, at the meeting, “A Google executive asked if they would consider taking the word ‘Muslim’ out of their name to avoid offending Pakistan’s government.”

The Ahmadiyya representatives refused. Zafar told Buzzfeed that the meeting ended without a resolution, and he told the Caravel that Google’s “solutions have been to rip us from our Muslim identity.” With no compromise, Google removed that Quran app from the Pakistan Play Store in October 2019.

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community offers a Quran app to its adherents on the Google Play Store.

In May 2020, said Zafar, the new Quran app went up on the Play Store; Pakistan flagged it in December, and Google took it down within days. Last month, the leaders of the Ahmadiyya community met with Google again to hash things out—but, said Zafar in an email to the Caravel, “Google stated it will not reinstate any content and has given no indication it will resist further demands from PTA to remove all Ahmadi content. They indicated that they had raised the human rights concerns to PTA but were told that they would have to stop their business in Pakistan if they did not remove the Ahmadi content.”

Khan thinks that was an excuse: “I sent a copy of our findings and detailed report by our technical team to Google over almost two weeks ago and they never responded. So it's clear to me that they just don't feel that this is an issue that they need to deal with.”

Google is “validating the basis of Pakistan’s persecution of our community, which is based on this notion that it's a crime to be an Ahmadi,” remarked Zafar.

Khan remained more neutral: “I think Google just doesn't want to wade into what they believe is a controversy fraught with risk insofar as they don't want to get on the wrong side of this issue with the government of Pakistan.”

In a follow-up email, Khan directed the Caravel to a press release his office put out at the beginning of February. Apparently, “between December 14-15, 2020, trolls in Pakistan infiltrated YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok and coordinated the upload of over 1,000 videos instructing viewers about how to alter Google’s search results related to the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community.”

A user named Ali bin Nazar shows his followers on Twitter how to report a Google search result as inaccurate. In this case, he is reporting what Google calls a “featured snippet” that aggregates probable results and shows the most likely answer. (Twitter, Ali bin Nazar)

His accusation has precedent. AP reported that, in a single day on Twitter in August 2020, “#AhmadisAreNotMuslims registered 45,700 tweets; #QadianisAreInfidel 50,600 tweets; #QadianisAreTheWorstInfidelsInTheWorld 32,600 tweets while #Expose_Qadyani_ProMinisters had 50,600 tweets.” (Ahmadis consider “Qadiani,” a reference to the Punjabi town that was home to their sect’s founder, a religious slur.)

It’s likely that Khan and Zafar would want to see those tweets taken down. But this hate speech is legal—and state-sanctioned. The Pakistani government’s neglect of its Ahmadi citizens threatens Ahmadi lives: in 2010, an attack on an Ahmadiyya mosque killed 93 people.

The Ahmadiyya Community press release quoted Khan, who said, “A failure to crack down on such propaganda techniques and online trolling can lead to untold crimes against humanity, not only against Ahmadi Muslims.” Khan accused “companies such as Google” of being “unwilling or unable to control mass-scale troll activity.”

Khan is rightly worried that Google is taking the wrong side: “Without explanation, Google has de-prioritized this very important human rights issue affecting our community—which is an issue affecting the global state of international religious freedom.”

The Freedom to Censor

Khan judged the consequences of Google’s acquiescence: “I think Google is embarking on a dangerous slippery slope that would lead to repressive governments freely censoring content of vulnerable religious communities without explanation, be those of Uighurs in China, Rohingyas in Myanmar, or Ahmadis in Pakistan.”

Zafar agreed: “If India makes the same request [of Google], and then Indonesia makes the same request, and then Saudi Arabia makes the same request, and then China makes the same request, then, one by one, we’ll be getting more and more censored.”

Khan and Zafar will be fine if they stay in the United States. Zafar didn’t really think that matters: “I know that they can't do anything to me.” But, he acknowledges, “there are countless members of our community that live in Pakistan that don't have that autonomy, and nor do they even have the ability to speak out.”

(Both Khan and Zafar mentioned that they probably shouldn’t try to visit their families in Pakistan, as it would put both them and their loved ones at risk.)

This isn’t just a problem for Ahmadis abroad looking to help Ahmadis at home. Repressive governments can now get the internet’s gatekeepers to turn a blind eye to their persecution of religious and ethnic minorities. These gatekeepers, companies like Google, become instruments of cross-border repression.

When Google takes down an app in Pakistan at the request of the Pakistani government, it sounds like a simple corporate exercise in respecting national sovereignty. But diving into some of these requests themselves reveals that “respecting national sovereignty” and adhering to local Pakistani law means sometimes enabling the further persecution of a religious minority. And so on, for other governments and other minorities around the world.

Fight or Flight

Khan and Zafar have been working with the U.S. government to see what they can do. Khan told the Caravel that the Ahmadiyya Muslim Congressional Caucus, a bipartisan group of Congresspeople, is currently formulating a letter addressing the situation. “There are a lot of members of Congress who are upset about this,” he said.

Khan also suggested that the U.S. government hold tech companies like Google accountable to both U.S. and international human rights laws while operating abroad. This way, Google would face consequences for neglecting human rights.

He also proposed that the U.S. government enact visa restrictions and Global Magnitsky sanctions, high-level sanctions against human rights violators, against Pakistani officials responsible for repression. Sanctioned individuals would have their assets frozen and their travel would be restricted; violating human rights would come at a cost. (Khan cautioned against general sanctions: the Pakistani government should not be conflated with the Pakistani people.)

Ultimately, tech companies like Google have a human rights problem. “The key players in this dangerous escalation,” said Khan, “are big tech companies who have the opportunity to resist this level of religious repression and digital persecution by protecting the content of the vulnerable.” Unless and until Google starts resisting, governments like Pakistan’s will only escalate their repression.

“We are the proverbial canaries in the coal mine,” Khan finished. “Our case will lead to other religious communities suffering in this way—this is a crucial time where all people of faith or no faith at all must stand on the right side of history.”

Google did not respond to the Caravel’s multiple requests for comment.