EU Infrastructure Plan Aims to Rival Belt and Road Initiative Through Digital Investment

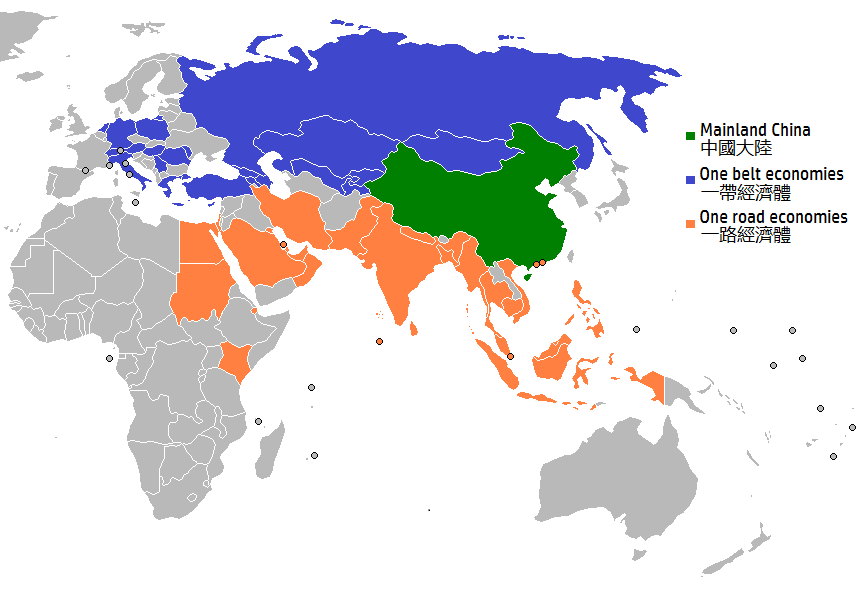

The Global Gateway looks to counter the influence of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (pictured), which holds increasing power within the European Union (Wikimedia Commons)

The European Union launched its strategy for the Global Gateway project on December 1. This endeavor intends to rival the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) by funding infrastructure for lower and middle-income countries without imposing the destructive debt characteristic to the BRI.

The EU’s statement regarding the Global Gateway focuses on digital, energy, and transportation infrastructure in order to “tackle the most pressing global challenges, from climate change and protecting the environment, to improving health security and boosting competitiveness and global supply chains.”

Kenneth Propp, adjunct professor of European Union Law at Georgetown University and senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, spoke with the Caravel regarding the EU’s infrastructure initiatives.

Propp discussed the growing impact of geopolitics in technology policy in Europe, articulating the announced plan as a European attempt to counter Chinese influence, but also as a genuine means to close the infrastructure gap in developing countries: “[Digital influence] is an area where the major powers of the world are competing with each other,” Propp said, “[the EU is] maneuvering for advantage, they’re trying to profile themselves with the developing world, as well as having completely legitimate altruistic interests… It’s really a mix of motives.”

The EU pledged up to €300 billion ($340 billion) over the next six years, which will come primarily through investments from member states, but will also include grants from the European Commission. Propp explained that Global Gateway financing has been grounds for criticism of the program, stating that the plan is simply “repurposing money that already exists in various other funds, having to do with sustainability, having to do with development finance.”

While much of the plan focuses on averting the impending crisis of climate change and softening the blows of COVID-19 in the developing world, the EU’s plan also focuses on the digital economy in order to counter the influence of Chinese investment in telecommunications and other digital infrastructure. Therefore, Propp did not determine the repurposement of funds to be completely invalid: “giving it all a coherent framework can be constructive…”.

Nevertheless, Propp noted that the funding was not sufficient to compete with the BRI: “the amount of money that is promised is nowhere near the scale of what the Chinese commit to their projects. They’re able to leverage state-owned banks. It remains to be seen if there will be private financing stepping up to match the EU money in these projects.”

Other international organizations plan to help the EU; two days following the EU’s announcement of the plan, the G7 committed to ally with the EU in order “to promote investments based on the Global Gateway strategy.”

Propp discussed European concerns that “valuable data might be harvested [through Chinese digital infrastructure],” and that the EU’s plan looks to secure what he referred to as “industrial data” of its own. The plan looks to fund fiber optic cable networks within both Africa and South America in order to create “usable pools of data,” keeping in line with other European initiatives such as the Data Governance Act and the Data Act. “There are a number of very important European global companies that are leaders in industrial manufacturing,” Propp said, “they want to be able to harvest the benefit of that sort of data.”

For now, the EU’s initiative does seem insufficient to adequately counteract the BRI; nevertheless, the Global Gateway does offer developing nations an alternative to reliance on China’s so-called “debt diplomacy.” The EU, through the infrastructure plan, hopes to offer the means to a more environmentally conscious and digitally-enabled world, while at the same time bolstering the economies of both target nations and member states.