Special Report: Mapping Vaccine Diplomacy

(Flickr)

For much of 2021, U.S. media sources publicized high-profile examples of Chinese “vaccine diplomacy” with countries across the Global South. Indeed, the Chinese government sent many of its domestically produced vaccines—made mostly by Sinopharm and Sinovac—to countries on every continent. Many of these countries were generally unable to pay for large quantities of Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, designed and made in the West.

The United States government sometimes portrayed Chinese vaccine donations as a self-serving plan to boost China’s reputation abroad. On its face, this accusation is meaningless: if Chinese policymakers donated their vaccines to Global South countries prevented from accessing Western vaccines due to their prohibitive costs, then it only makes sense that opinions of China across the Global South should rise.

The more interesting question is whether or not there are any patterns present in the global distribution of Chinese vaccinations. Were most Chinese vaccines sent to China’s economic and political allies, to potentially reinforce their dependence on China? Or did vaccines go to countries with limited connection to China before 2021, perhaps to create goodwill where little existed before?

To answer these questions, we study the relationship between Chinese vaccine disbursement, Chinese foreign investments, and U.S. foreign investments. We hypothesize that Chinese vaccine disbursement should be higher in countries that received higher amounts of Chinese investment since 2016, around when China’s Belt and Road Initiative was solidified. Taken together, these factors can serve as a powerful indicator for how China approaches its relations with other states, who it courts, and who it leaves out. In turn, there may be some degree of correlation between vaccine diplomacy, China’s investment spree, and how other states handle the increasingly consequential China question.

Our data on Chinese foreign investments comes from the American Enterprise Institute’s Global Investment Tracker. We measure all investments as a percentage of host country GDP. Moreover, our data on Chinese vaccine donations is courtesy of Bridge Beijing, a China-based economic development consultant group. They maintain a Chinese vaccine tracker, and we owe them a debt of gratitude for allowing us to use their data. All vaccine distribution data is as of December 14th, 2021, and the dosage of vaccine donation is scaled according to each country’s population. And, later in this piece, we check our findings against U.S. foreign investment figures since 2016, data for which comes from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. We also measure these investments as percentages of host country GDPs.

The Caravel has produced an interactive data visualization that aggregates all the variables in question, parses their relationships, and zooms into regions of interest. Moreover, it also takes into account the interplay between China’s sweeping BRI and its investment portfolio worldwide. Feel free to play around with our data. Or scroll down to read our interpretation of the visuals in front of us.

Regional Trends

Measuring investment as a percentage of GDP and vaccine donations per million people, we find that China both invests aggressively and doles out large vaccine donations in both Southeast Asia and Latin America. And, perhaps contrary to popular perceptions, Chinese presence in Africa is an inconsistent patchwork of investments and vaccine donations; few countries receive high levels of both. Finally, Chinese presence in the West (Europe, North America, and Australia/New Zealand) is almost entirely dominated by investments. To more closely examine regional trends and nuances, we zoom in on South and Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa.

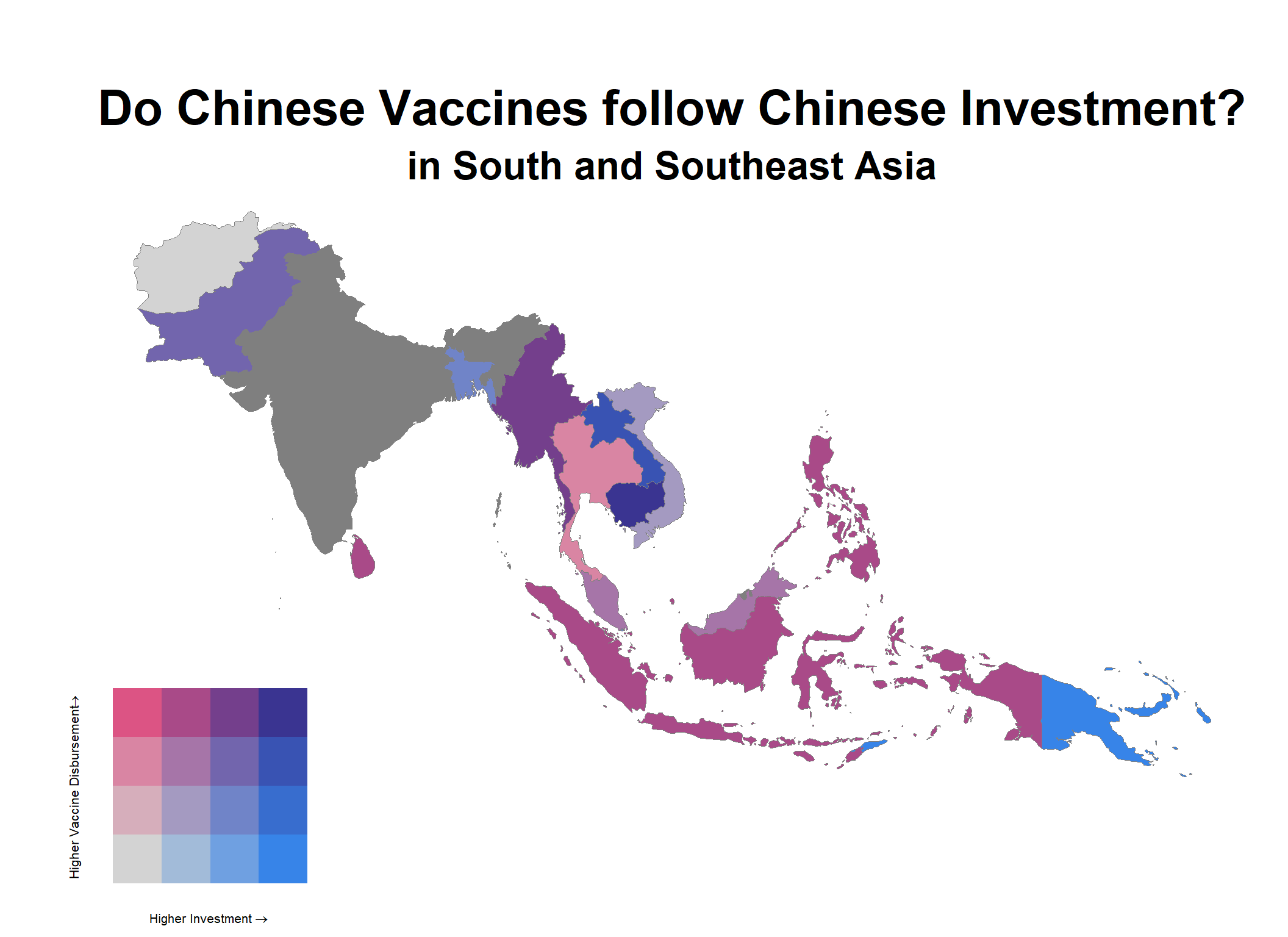

South and Southeast Asia: Rewarding Some, Cold Shoulder for Others

One country in Southeast Asia quickly jumps out as an outlier—Cambodia, which gets generous doses of vaccines and lucrative investments. Meanwhile, countries such as India and Afghanistan don’t get a lot of either vaccines or investments from China when adjusted for GDP and population. (India received a grand total of 0 vaccines from China.) The rest of the countries in the region, which are either neutral or increasingly friendly vis-à-vis China, get a good amount of both. Ultimately, because of the incredibly diverse vaccine distribution and investments landscape, this bivariate map looks a bit difficult to decipher.

Nevertheless, Chinese vaccines and investments considered in conjunction with one another can be a viable predictor for how South and Southeast Asian states calibrate their China policy. Indeed, the big winners of both vaccines and money, Cambodia and Laos (and to a lesser extent, Myanmar), are all drifting closer towards China’s orbit. Meanwhile, states that get relatively less of either (i.e. Vietnam and India) are China’s potential regional counterweights.

Visualizing vaccine diplomacy and investments in South and Southeast Asia separately.

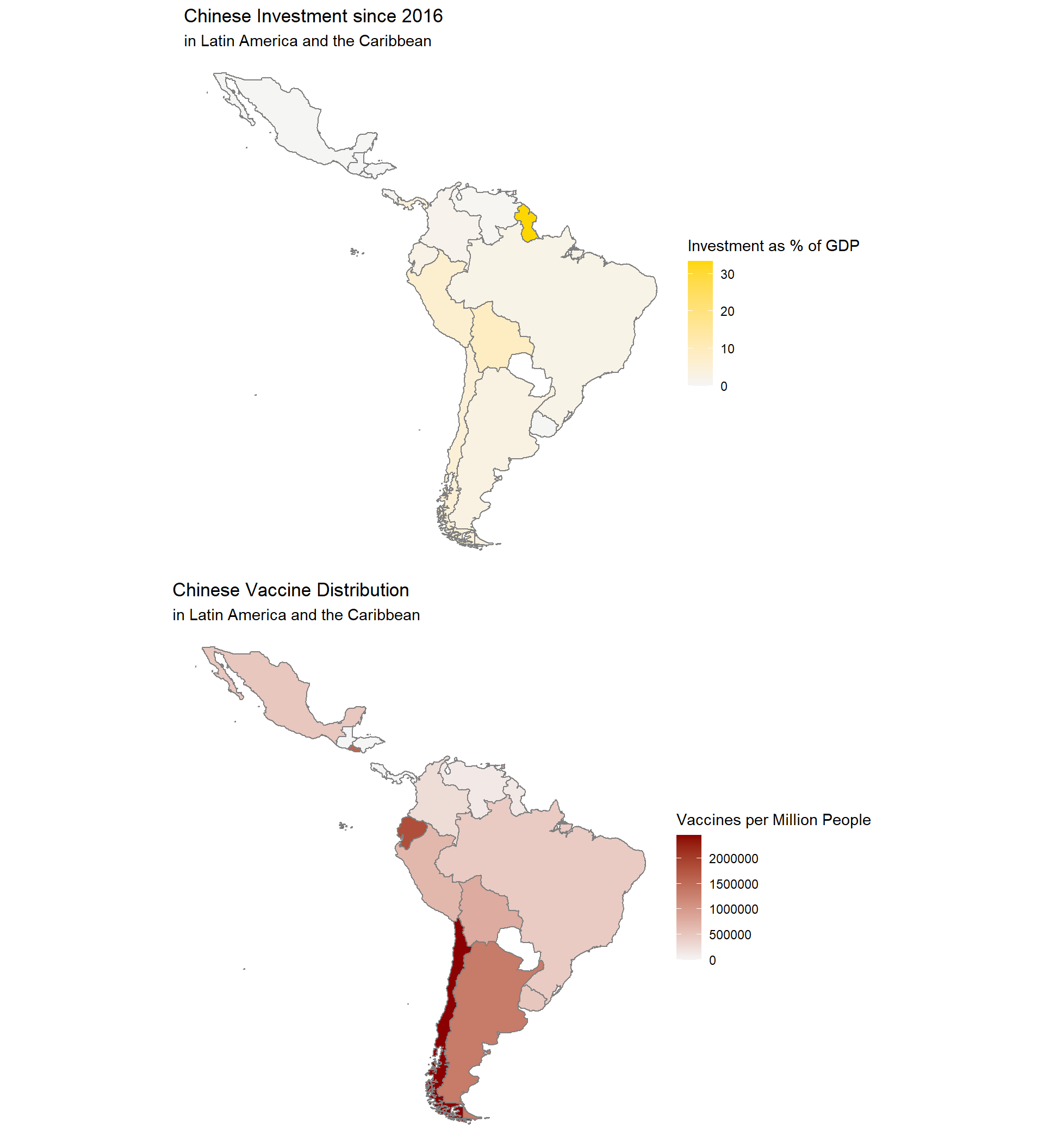

Latin America: An Uneven Patchwork

In Latin America, Chinese vaccine diplomacy and investments don’t seem to be following a clear pattern. Chile and Argentina seem like big investment and vaccine winners here when we adjust for population and GDP. Peru gets more investment than vaccines; Bolivia and Uruguay get more vaccines than investment; Brazil and Colombia get a medium amount of both. Meanwhile, Mexico, the Central American states, and Venezuela are getting relatively less of either, even while their relations with China have remained cordial.

Visualizing vaccine diplomacy and investments in Latin America separately.

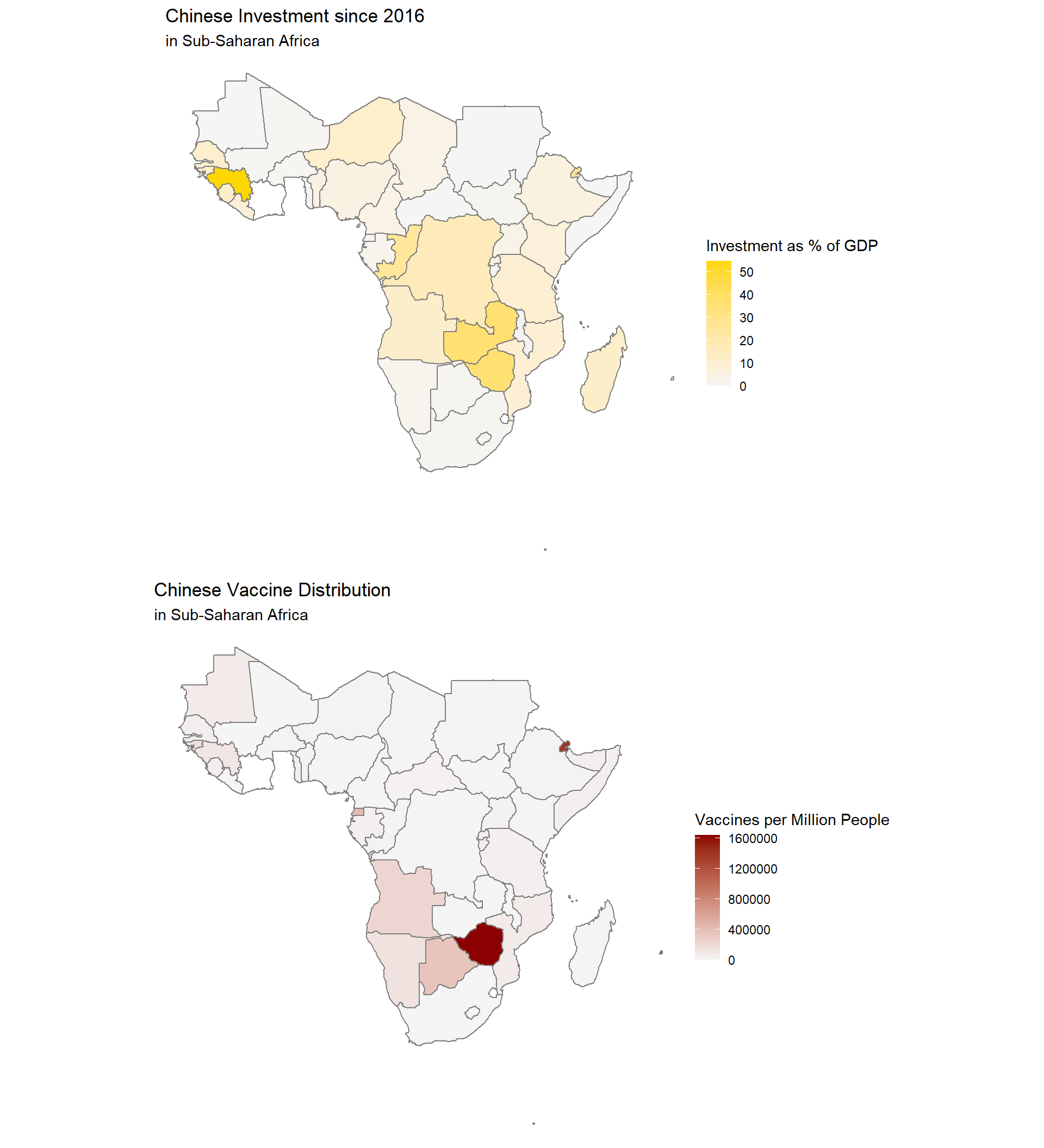

Sub-Saharan Africa: Rising Rapidly on China’s Radar

Comparing investment and vaccine volumes to Africa over time.

When we mapped vaccines and investments in Sub-Saharan Africa last fall, our results seemed to fall short of all the buzz surrounding China’s burgeoning influence on the continent. Africa was not receiving as much of either resource compared to other regions of interest, such as Southeast Asia or Latin America. However, comparing the visualizations from last fall and those from this spring tells the story of a continent that is becoming more salient on China’s foreign policy radar. Indeed, both vaccine and investment volumes destined for Sub-Saharan Africa have seen notable increases.

Countries on Sub-Saharan Africa's Northwest coast and Southern countries seem to receive both high amounts of vaccines and investment. Angola and Zimbabwe, Chinese partners in development as of late, are unsurprisingly dark purple. The Democratic Republic of the Congo, interestingly enough, has not received many vaccines at all—despite the fact that it is an outpost for Chinese mineral extraction in the region.

Visualizing vaccine diplomacy and investments in Africa separately.

Zimbabwe received the most Chinese vaccines per capita than any other country in Sub-Saharan Africa. Djibouti was the only other country that came close. The rest of the continent, it seems, is not getting much in the way of Chinese vaccine diplomacy. Chinese investment around the continent is far more distributed.

One Belt, One Road, Two Doses

Not all investments are created equal. Financial sector and real estate investments in the United States are far different from mining investments in Africa and Latin America, or logistics investments in Southeast Asia.

Chinese companies invest in lots of different industries. In developing countries—concentrated in Latin America, South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Eastern Europe—energy investments totally dominate the investment mix, with metals close behind. In richer economies, and in Central Asia, real estate and transport investments dominate. It’s obvious that the character of Chinese investments varies around the world. How might that affect vaccine distribution?

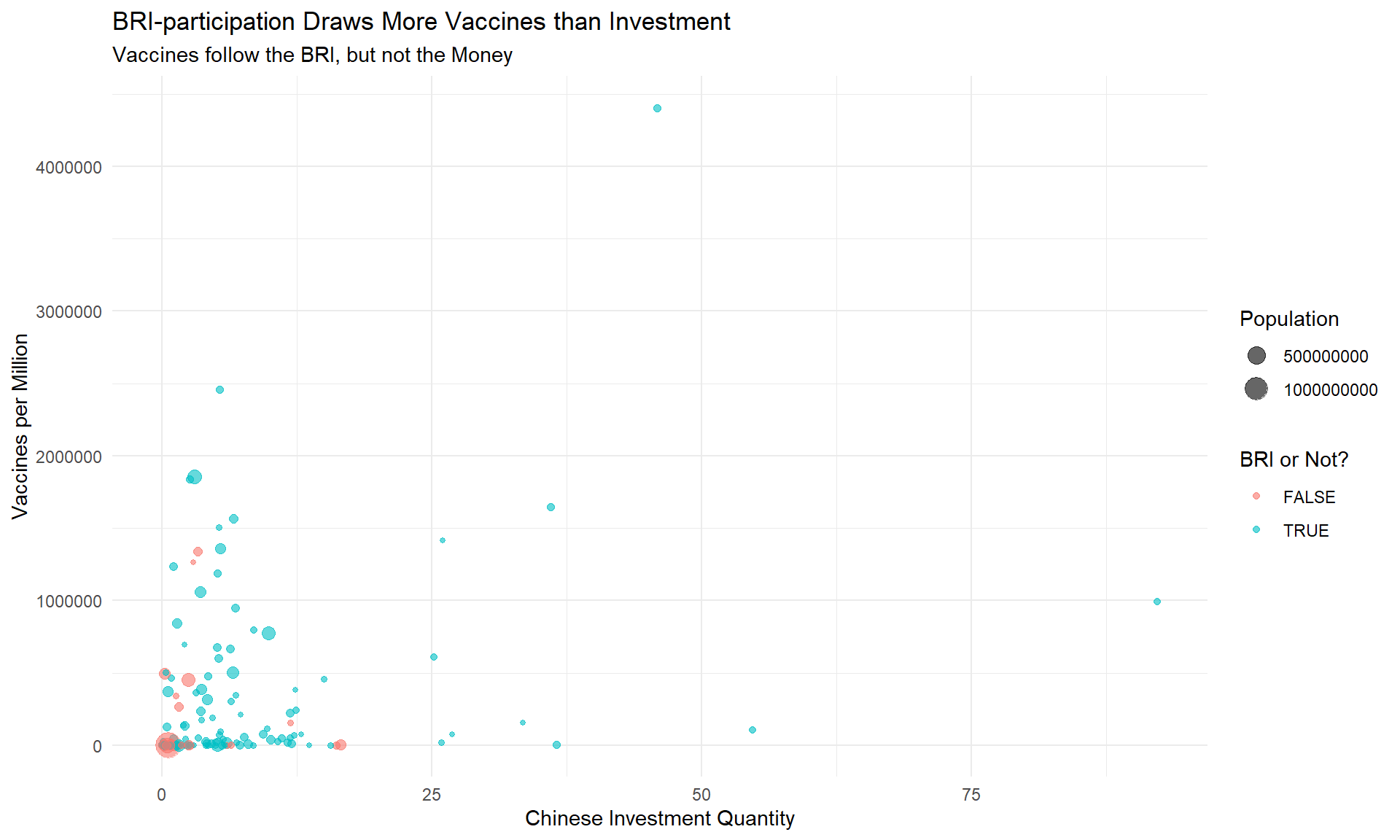

Earlier we looked at South and Southeast Asia and Latin America as loci for Chinese investment and vaccine distribution. Both these regions have high amounts of Chinese investments in energy, metals, and transport. Latin America has a higher share of energy and metals investment, to be sure. Investment in South and Southeast Asia is more diversified, though transport takes a larger share in both regions relative to Latin America. We can conjecture that, in both these regions, resource extraction and the transport logistics matter a lot for Chinese investors. We also know that both these regions are major parts of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Does Belt and Road status impact where vaccines and money go?

Off the bat, it looks like BRI countries get far more vaccines than investment. Vaccines follow the BRI. Do vaccines also follow the money? Probably not: save for some wild outliers, a negative relationship seems to hold between vaccine donations and Chinese investment.

This could have something to do with investment breakdowns by region. Investment in transport, technology, finance, and real-estate is often a lot more pricey than investment in energy and metals. Indeed, if we return to that stacked bar chart but use absolute scaling, we see the following.

Vaccines won’t follow the money, considering that most of that money goes to mostly non-BRI countries in the Global North. No other region has as diversified an investment mix as the Global North does.

Within BRI countries, though, the story is different. Save for Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East and North Africa, where no non-BRI participants are in the sample, BRI participants get more vaccines than non-BRI participants. The conclusion here is likely that the diplomatic ties that BRI arrangements promoted also facilitated vaccine disbursement. This excludes many Global North countries immediately.

The United States

Membership in the BRI clearly influences where vaccines go. But if there’s one thing the pandemic has done, it has been to expose how at odds China and the United States can sometimes be. Perhaps China is sending vaccines to countries that aren’t receiving as much U.S. investment, to position itself as a worthy partner that looks out for those countries’ interests. Or maybe China is sending vaccines to countries that are receiving lots of U.S. investment – to show that the U.S. isn’t the only cool country in town. Do Chinese and U.S. investments even go to the same places?

Given the data we have, it looks like Chinese vaccines go where U.S. investment clearly doesn’t—except for Latin America and, to a small degree, Southeast Asia. We also find that Chinese investment and U.S. investment only overlap significantly in Western Europe, Australia, and Latin America. To be sure, our U.S. investment data from the BEA also excludes a decent few countries, presumably for their insignificant amounts of investment. We do not believe that the presence of that data would change this finding.

Conclusion

Vaccines don’t follow most of the money. To predict where China might continue to deliver its vaccines, look to its diplomatic arrangements for investment, such as the BRI, and look where the United States isn’t turning its investments towards.

To be sure, Chinese investments abroad are often state-sanctioned. This statement is an overgeneralization of Chinese foreign investment, but, that being said, the sectors Chinese firms invest in across much of the Global South—primary production sectors, including mining and energy—are often state-led sectors in China. This observation suggests that the Chinese state has a lot of discretion about where foreign investments end up. At a more granular level, we wonder if more vaccines go to states with higher amounts of investment from Chinese state entities and development banks.

Over the course of our investigation, we found that the United States and China are definitely competing to invest in Latin America and South and Southeast Asia. Significant U.S. and Chinese investments in both regions has led to outsize Chinese vaccine disbursements there. Interestingly enough, the U.S. State Department’s vaccine disbursement website lauds the U.S. government’s own vaccine donations to those regions. The U.S. has been engaging in its own “vaccine diplomacy,” too.

If you have any questions about our data or analysis, do not hesitate to email Advait Arun (aa2103@georgetown.edu) and Alex Lin (al1439@georgetown.edu).

Niger announced withdrawal from a key counterterrorism task force at the start of April, putting regional stability in jeopardy in the Sahel.