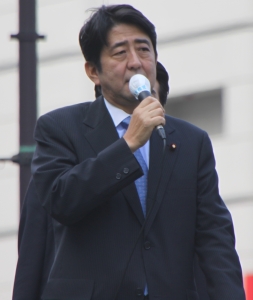

Abe Expected to Call Snap Election

As rumors swirl about Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe calling a snap election in December, it is a good opportunity to reflect on both the potency and the folly of calling snap elections in Japan, where voters have long been disillusioned by the lack of clear ideological choice between parties and recent elections have been characterized by extreme “swings,” cycle after cycle. In Japan’s bicameral parliamentary system, the timing of elections is not quite as predictable as the rigid two- and four-year cycles that we have in the US presidential system. While the upper house, the House of Councillors, is elected on a regular three-year cycle (usually held in mid- to late-July), the lower house, the House of Representatives, can be dissolved by the prime minister – or by the parliament with a vote of no confidence – in a “snap election” before they serve out their maximum term of four years. In most parliamentary systems, prime ministers try to use their constitutional authority to call a snap election when they have the public support to win a “popular mandate” that they can use to push through unpopular policies.

As rumors swirl about Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe calling a snap election in December, it is a good opportunity to reflect on both the potency and the folly of calling snap elections in Japan, where voters have long been disillusioned by the lack of clear ideological choice between parties and recent elections have been characterized by extreme “swings,” cycle after cycle. In Japan’s bicameral parliamentary system, the timing of elections is not quite as predictable as the rigid two- and four-year cycles that we have in the US presidential system. While the upper house, the House of Councillors, is elected on a regular three-year cycle (usually held in mid- to late-July), the lower house, the House of Representatives, can be dissolved by the prime minister – or by the parliament with a vote of no confidence – in a “snap election” before they serve out their maximum term of four years. In most parliamentary systems, prime ministers try to use their constitutional authority to call a snap election when they have the public support to win a “popular mandate” that they can use to push through unpopular policies.

However, in Japan, for the past decade, prime ministers have more often been forced to resign due to their own low approval ratings rather than have the opportunity to call for a strategic snap election benefitting from their personal political capital. The most famous example of a Japanese prime minister using a snap election in recent times is Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro, who used his powers to call a snap election in 2005, only two years out from the last one held in 2003. In the 2005 general election, his party, the conservative Liberal Democratic Party, picked up 66 new seats for a total win of 236 seats – more than enough seats to push through his postal privatization plan, which was deeply unpopular among members of his own party. After the dramatic showdown between Koizumi’s reformers and the stalwart defenders of the Post Office, the next House of Representatives election was held four years later, as expected, in 2009.

The most recent House of Representatives election in December 2012, only three years later, was the result of a political deal between then-Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda and Shinzo Abe: Noda offered to dissolve the parliament early if the LDP agreed to pass a bill on electoral reform in the next parliamentary session. In retrospect, the results were disappointing for Noda, but at the time, analysts observed that setting the next election so early was an astute political move, a “pre-emptive” strike against the “third force” parties that were beginning to coalesce, such as the Japan Restoration Party based in Osaka and Ishihara Shintaro’s ultranationalist Sunrise Party. Observers expected there to be no clear-cut majority for either the LDP or the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), but that the surprise announcement would be enough to ruin the chances of any third party challengers. Yet, the LDP won that lower house election, picking up 176 new seats for a total of 294. Abe at the time expressed cautious optimism, as he knew the historic victory was more a repudiation of the DPJ than an endorsement of the LDP: he commented, “We recognize that this was not a restoration of confidence in the Liberal Democratic Party, but a rejection of three years of incompetent rule by the Democratic Party.” However, the LDP victory in the upper house the following summer has shown that the people’s preference for Abe may be more than just a fluke.

Abe may call a snap election in December in order to gain the mandate he needs to delay the second tax hike promised in a 2012 deal – or at least gain some more time to “study the matter” and postpone a final decision. According to the 2012 deal, the tax hike must take place October 2015; Abe is considering postponing it by a year to a year-and-a-half. When in April, the government raised the consumption tax from 5% to 8%, the economy took a 7% hit over the April-June quarter. The most recent economic analysis shows that the Japanese economy decreased by an annualized rate of 1.6% in the July-September quarter. The second tax hike is supposed to raise the rate from 8% to 10% and some of Abe’s advisers worry about the raise’s economic impact. The other political consideration that Abe must weigh is domestic support: 70% of Japanese oppose it. Yet some LDP politicians as well as Ministry of Finance officials want to prioritize dealing with Japan’s immense public debt and push for Abe to keep his promise. In some ways, there are interesting parallels to Koizumi’s snap election: Abe is trying to use public support to bend contrary elements within his own party to his will. He is also confident in his victory – in recent polls, the LDP has 40% support, while the DPJ trails significantly behind with 5%.

Though Abe might lose a few seats, he is unlikely to lose electoral control. However, tying the tax delay to the election may backfire politically. As Gerald Curtis, a Columbia University specialist in Japanese politics states, comments, “An election done out of weakness does not strengthen the incumbent.” In fact, it could be an “admission” that Abenomics is not working as well as it was touted it would. That is exactly what the DPJ is calling LDP out for. The DPJ’s Secretary-General, Yukio Edano, couldn’t resist a jibe at the LDP: “Because of failed economic policies, most people aren’t in a position to accept a bigger burden.” It is implied that “failed economic policies” refers to Abenomics. The Mainichi Shinbun has recently criticized Abe’s handling of the election in a withering editorial, “Ruling parties dodging responsibility with move to general election.” The editorial criticizes Abe for his “ham-fisted” tactics – relying on the election to solve this serious, thorny problem instead of having an open, public debate about it – which “[discredits] the political process.”