An Aging Nation: A Bleak Future for South Korea

Are South Koreans ever going to be extinct? Although this question sounds bizarre, the National Assembly Research Service of South Korea recently raised this possibility. The Research Service recently reported that, if the country’s current birthrate of 1.19 children per woman continues, South Korea’s population would decrease to one-fifth of the current population in the next 120 years and will eventually reach zero by 2750. While the low birthrate is a complicated problem, its danger is growing at an alarming speed.

Low birthrate emerged as a serious challenge to South Korea in the last two decades. Before 1960, South Korea suffered from overpopulation with the birthrate around 5.5 to 6.5 children per woman. To a country left with nothing but ruins from a civil war, the population explosion posed an obstacle to quick industrial development and improvement in the standard of living. In 1961, the government adopted population control policies that recommended two or less children per household and encouraged migration to other countries. The policies proved effective until the 1980s, when the birthrate was slightly less 3.0 children per woman. However, even after the birthrate fell below 2.0 in the 1990s, the decline continued to accelerate. In 2013, the country’s birthrate hit the record-low of 8.6 newborn children per 1000 people.

Low birthrate emerged as a serious challenge to South Korea in the last two decades. Before 1960, South Korea suffered from overpopulation with the birthrate around 5.5 to 6.5 children per woman. To a country left with nothing but ruins from a civil war, the population explosion posed an obstacle to quick industrial development and improvement in the standard of living. In 1961, the government adopted population control policies that recommended two or less children per household and encouraged migration to other countries. The policies proved effective until the 1980s, when the birthrate was slightly less 3.0 children per woman. However, even after the birthrate fell below 2.0 in the 1990s, the decline continued to accelerate. In 2013, the country’s birthrate hit the record-low of 8.6 newborn children per 1000 people.

Primary causes for low birthrate include rise in the number of unmarried people. From 1990 to 2013, the average marriage age for men and women rose from 27.8 and 24.8, respectively, to 32.2 and 29.6. Even those who are married choose to give birth at older ages. It is true that the women’s participation in the economy and the new attitude towards life that values building career and enjoying freedom have contributed to this trend. However, economic factors rather account for young people’s late marriage and childbearing choice. According to a survey in 2012, top three reasons for not marrying, excluding being too young, were the concerns for the marriage expenditure, low income and housing prices. The top reason for not giving birth was high childrearing expense.

Why is raising a child so difficult in Korea? First, the young generation suffers from unemployment and rising house prices. On average, housing prices increase by 11.8% annually. The rising housing price is a serious concern for the middle class, who have to save all of their incomes for more than 3 years to rent a house. Second, the country’s notorious education system maintains high demand for expensive private education. In 2014, the national total spending for private education was USD $18 billion, taking up more than 10% of the average disposable income per each household. However, the government’s level of support for education remains low. Among the OECD members, South Korea is one of the countries with very high college tuition but the lowest level of public expenditure for tertiary education as a percentage of GDP. The recent buzzword “3 No Generation”, which refers to the current young generation who gave up dating, marriage and childbirth, aptly represents this trend.

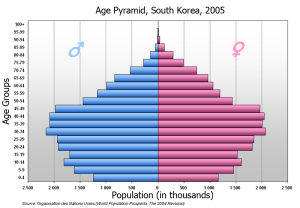

Experts expect the falling birthrate to cause severe challenges in various sectors. First of all, following the aging of labor force, industries that require physical labor, such as agriculture, fisheries and manufacturing, would suffer from decrease in labor productivity. Secondly, young people will have even less public resources for themselves. The South Korean government estimates that, by 2040, the number of people over the age 65 per every 100 economically active people will increase to 57 people. Consequently, welfare programs for the aged will take up a great portion of the country’s budget, while the economic responsibility of young people will be heavier than ever. Moreover, as the number of soldiers decrease, the national defense power would decline as well. If the relationship with North Korea fails to improve, a shortage of soldiers will exacerbate the national security problem.

The main causes of the low birthrate suggest that the keys lie in economic and welfare policies. As they are in many other countries, economic and welfare policies are the main dividers among politicians and voters in Korea, who argue in favor of different economic policies that help different interest groups of people. However, it seems that there is no more time to lose. By the time the problem has begun to undermine the basis of the country’s economyic and security, which experts foresee to be in the next several decades, it would be too formidable to address. South Korea should begin prepare itself with coherent and effective policies with a long-term perspective for its national interest, if not for its own survival.