Brazil Seeks Twenty Year Freeze on Government Spending

On October 25, PEC 241, a measure by the Brazilian government to freeze government spending, passed its second vote in the House of Representatives, and now awaits two votes in the Senate before it can become law. The constitutional amendment represents President Michel Temer’s attempt to address the increasingly problematic government debt and stimulate the Brazilian economy. Specifically, he proposes a strict, twenty-year government spending cap as a remedy to the country’s economic crisis. The constitutional amendment would cap annual spending by the federal government’s three branches at the previous year’s value, adjusted for inflation. PEC 241 would attempt to cut down a budget that, under 13 years of management by the Worker’s Party (PT), has steadily increased. Government debt has risen by 250 percent since 2008, while the GDP in US dollars, after a dramatic shrink last year, is nearly back at its 2008 level.

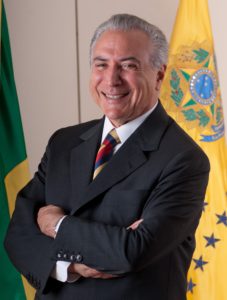

President Temer, who recently secured power for his PMDB party after the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff, argues that the amendment represents a hard-but-necessary pill to swallow for the country. According to Temer, it would restore international and private sector confidence in Brazil’s markets. He tried to make that case to fellow leaders of the emerging nations at the recent Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa (BRICS) summit in Goa, India, as well as to Christine Lagarde, Managing Director of the IMF. After a meeting with Brazil’s Finance Minister, Lagarde issued a statement approving of the reforms and expressing confidence in their effectiveness.

Critics, however—both economists and opposition party leaders—see several problems with the measure. Some argue that it doesn’t go far enough, as it fails to cap welfare spending, which makes up 40 percent of the national budget. The Temer government has acknowledged this shortcoming and indicated that they plan to tackle welfare reform once PEC 241 has successfully passed.

Others worry that it will have damaging social effects, both because it will freeze constitutionally mandated spending on education and health and prevent increases in the minimum wage above the rate of inflation. The Justice Ministry has even released a statement calling the amendment unconstitutional because it interferes with the independence of each of the three branches of government. Finally, some argue that, rather than ensuring economic recovery, it may impede growth in the long-run by preventing the government from investing returns back into the economy once it moves past the current crisis.

The main cause for concern appears to be the measure’s longevity; the amendment allows for a revision of the cap after 10 years, but it would still dramatically restrict government spending for two decades. President Temer is currently governing without a strong democratic mandate, given that he rose to power through a contentious impeachment and not an election of his own. In addition, he is ineligible

to run for reelection in 2018, so he will only occupy the presidency for a maximum of two years. If his measure passes, however, his party’s neoliberal policies could affect how the Brazilian government tackles social issues until 2037. While it’s clear Brazil’s fiscal policy is in need of a fresh perspective, many are hesitant to give Temer such far-reaching reign in dictating future policy.