Dueling for the Desert by the Sea

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, the Netherlands, declared itself competent to judge the validity of Bolivia's claim to access the Pacific Ocean. Bolivia's claim argues that Chile failed to comply with a 1904 treaty that grants commercial ocean access to landlocked Bolivia. Chile responded with an objection that the dispute was not within the jurisdiction of the ICJ. In Thursday's ruling, the ICJ asserted that it can order the two countries to negotiate if it sees so fit. The declaration may grant Bolivia the opportunity for a long-awaited outlet to the sea. For Chile, it means that the ICJ will be involving itself in a dispute that has already been resolved.

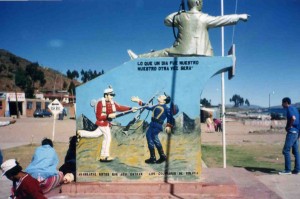

The Lost Atacama

The 1879-1883 War of the Pacific, the original source of two of Chile's disputes in the ICJ — one with Peru as well as the one with Bolivia — originally began over a disputed 1866 treaty between Chile and Bolivia concerning the Atacama Desert. Both countries had the right to mine the Atacama between the 25th and 23rd parallel, and Spain marked the border between the two nations at the 24th parallel. Protests by Chilean businesses against the Bolivian management of properties in the Atacama and Bolivian taxation they deemed unfair prompted Chile's army to enter the territory on the grounds of protecting its national interests. The conflict pitted Chile’s stronger army and navy against the weaker combined Bolivian-Peruvian forces, ending with a military triumph for Chile. Its 1904 resolution in the Treaty of Peace and Friendship gave the disputed Atacama territory stretching to the Pacific coast to Chile but allowed for Bolivia to set up customs offices in Chilean ports, ask for construction of a railroad from the port of Arica to La Paz, and have free right to transit goods through northern Chilean territory to the ocean.

Fate, however, has not worked in Bolivia’s favor. The ceded Atacama territory proved to be rich in both nitrate, which sustained Chile's economy until the creation of industrial nitrate in 1909, and copper, which accounted for 19% of the country's GDP in 2014. Today, Chile's GDP in terms of purchasing power parity ranks 44th in the world, whereas landlocked Bolivia's ranks 94th. While some would argue that the vast discrepancy is an issue of differing economic policies, Bolivia’s weaker economy can be traced to access to international markets and lack of resources that many argue can be solved by regaining access to the sea. It is also a deep issue of national pride for both nations; Bolivians still maintain a navy and Chileans see the Atacama as an integral part of their territory.

Moving Forward

In 1975, Chile's dictator Augusto Pinochet offered Bolivia a sliver of territory as access to the sea in exchange for an equal-sized territory from inland. Bolivia rejected the treaty on the grounds that it unfairly claimed land in Peru, which to this day remains a staunch Bolivian ally. A later attempt at negotiations between the two countries in 1987 also failed. Today, Chile's military and naval capacities still exceed those of its neighbor, meaning that war is out of the question for Bolivia. However, hopes are high in Bolivia that the ICJ and international pressure may push Chile into negotiation. From Chile's perspective, however, the issue has already been resolved given that Bolivia rejected the 1975 treaty, signed onto the 1904 treaty, and is already allowed commercial access to the sea. Chileans also have claims to territorial sovereignty, given that the territory is now an integral economic and cultural part of Chile. Chile now has until July of 2016 to make its case to the ICJ. Nevertheless, a quick resolution is not to be expected. The two countries have furthermore closed their embassies and are not on formal speaking terms for any form of negotiation.