#JeSuisNigeria: Ongoing Terror in West Africa

This week, as over a million people, including many world leaders, united to march on the streets of Paris in response to last week’s terrorist attacks, Boko Haram continued its murderous rampage in northern Nigeria. In what has been labeled as possibly its deadliest attack, an estimated 2,500 civilians were killed as militants tore through the towns of Baga and Doron Baga near the Chadian border. According to witnesses, Boko Haram soldiers spared no one, slaughtering children, the elderly, and even a woman in the process of childbirth. Satellite imagery taken before and after the attacks shows just how destructive the group was, with entire blocks of buildings razed to the ground. While Boko Haram has terrorized northern Nigeria for several years now -- and killed over 2,000 people in the first half of 2014 alone -- last week’s killings were of a new level of destruction. The group has even been accused of resorting to child suicide bombers.

This week, as over a million people, including many world leaders, united to march on the streets of Paris in response to last week’s terrorist attacks, Boko Haram continued its murderous rampage in northern Nigeria. In what has been labeled as possibly its deadliest attack, an estimated 2,500 civilians were killed as militants tore through the towns of Baga and Doron Baga near the Chadian border. According to witnesses, Boko Haram soldiers spared no one, slaughtering children, the elderly, and even a woman in the process of childbirth. Satellite imagery taken before and after the attacks shows just how destructive the group was, with entire blocks of buildings razed to the ground. While Boko Haram has terrorized northern Nigeria for several years now -- and killed over 2,000 people in the first half of 2014 alone -- last week’s killings were of a new level of destruction. The group has even been accused of resorting to child suicide bombers.

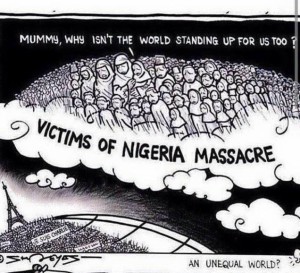

Despite the brutality of these attacks, media coverage has been largely directed to the devastating yet smaller-scale shootings at the office of the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, where 12 people were killed. This perceived lack of reporting on Nigeria has prompted social media users to tweet “#JeSuisNigeria” to raise greater awareness about the violence perpetrated by Boko Haram.

Why have these two incidents produced such different reactions?

One reason may be the fact that such a direct form of terrorist attack in France had not occurred in 50 years, while northern Nigeria has been subject to Boko Haram’s violence since 2009. Yet the scale of destruction in Baga and Doron Baga is equally unprecedented, and deserves equal coverage.

Another may be that the Charlie Hebdo attacks were also symbolic: the terrorists were challenging the satirical newspaper’s right to freedom of speech in a country often referred to as the birthplace of democratic ideals. The phrase “Je Suis Charlie” and the demonstrations in Paris this past week were intended to show solidarity in defense of free press. Charlie Hebdo’s right to depict the Prophet Mohammed in its caricatures has been a key point of contention among the public.

But while thousands have taken to social media to argue about free speech in a democracy such as France, much less concern has been directed towards Boko Haram’s insistence on enforcing Islamic law in democratic Nigeria. While it is fair to argue that Nigeria’s civil rights’ record has been shaky at best, the country is still, in principle, a democracy under civilian rule. During Nigeria’s many years of military dictatorship, human rights and liberties were routinely trampled upon, and only through the perseverance of many ordinary citizens were these freedoms eventually returned through the introduction of democracy. The notion that a particular group can force its beliefs upon others via the threat of violence should be contended in any democracy, regardless of its level of human development.

Politics is also an important factor. In 2014, President François Hollande’s approval ratings were lower than those of any president in French history. Mr. Hollande’s Socialist Party has also faced rising competition from the anti-immigrant, right-wing rhetoric of the National Front party, sparking conversation about the basis of French identity. The recent attacks have served as a rallying call across France, which would only compel Hollande to take a more active role in the demonstrations.

Meanwhile, with national elections coming up next month in Nigeria, President Goodluck Jonathan has little incentive to further publicize the ongoing strife with Boko Haram. Mr. Jonathan publicly condemned the Paris attacks within 24 hours of the outbreak, but did not acknowledge the violence in Baga even a week after its onset. His approval ratings have been sliding from 43% in 2012 to 35% in 2014. It comes as no surprise that Mr. Jonathan’s government is keen to downplay the seriousness of Boko Haram, especially since the Nigerian military has had limited success in halting the militants’ progress. While some sources estimate the death count of last week’s killings at around 2,000, the government claims that the numbers are only 150. Such a large difference between these estimates could partially be attributed to the administration’s desire to keep the media spotlight out of the region.

While these reasons are not the only ones for the apparent lack of coverage, they do highlight important distinctions between the situations in France and Nigeria. But it should not excuse the fact that Boko Haram’s insurgency will only get worse without greater worldwide attention and intervention.