South America Prepares for El Niño’s Tantrum

Every few years, December in South America gifts the region with more than yuletide greetings. Occurring at sporadic intervals, El Niño is a weather phenomenon that, in its most direct form, raises oceanic temperatures in the Pacific Ocean from Chile to Alaska. Branching out from the epicenter, El Niño indirectly impacts a variety of facets of life in South America.

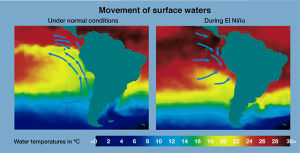

El Niño, named as an allusion to the birth of Jesus of Nazareth, is an irregular climate phenomenon that warms the waters around the western coasts of the Americas. First, trade winds push warmer currents from Indonesia and Australia across the Pacific. Then, as those currents are pushed across into the Americas, the water temperatures rises, impacting current strength, fisheries, and rainfall levels.

Since its first recorded occurrence by European colonists in the mid-sixteenth century, El Niño has occurred at relatively stable intervals, although at varying strengths. The most recent event happened in 2010 during the Vancouver Winter Olympics, but none of serious strength have affected the Western Hemisphere since the 1997-1998 when over 20,000 people were killed and nearly $97 billion of damage was done across the globe.

While predicting the exact year when El Niño will strike has proven difficult, climatologists at the National Academy of Science of the United States of America asserts there is a 76 percent probability that a moderately strong El Niño will occur by the end of the year.

However, El Niño holds such an acute influence over international economics that the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has released its own report placing the odds of an El Niño at slightly over 50 percent. Numerous El Niño researchers have challenged NOAA’s findings as overly conservative and indicative of attempts to prevent panic. Historically, when farmers expect an imminent El Niño, food prices tend to spike significantly throughout Latin America.

While the threat of El Niño will raise prices due to producer anxiety, when ocean temperatures actually rise food stores are directly impacted. Countries along South America’s Pacific border, such as Chile and Peru, earn a significant portion of their yearly incomes from the fishing industries that thrive in their coastal waters. The cooler waters attract phytoplankton, an organism at the bottom of the food chain that draws large numbers of small fish, such as anchovies, to the South American coasts allowing Peru and its neighbors to sustain a large fishing industry.

The rising water temperatures that hallmark El Niño, however, push the phytoplankton and the fauna they support into the colder depths beyond the fishers’ range. While other fish flock to the warmer waters in the phytoplankton’s place, the replacement fish do not sustain the fishery demand leading to overfishing, higher prices, and starvation.

Despite the negative impact El Niño has had on these nations’ fishing industries, it has proven to offer a positive outcome for the environment. To avoid mass starvation during an El Niño, countries like Peru have begun implementing bulwark overfishing quotas in order to maintain the fishing industries and the national economy.

The effects of the warmer coastal waters do not confine themselves to the immediacy of the Pacific. Typically, in South America as the El Niño phenomenon causes ocean temperatures to rise, heavy rains fall along coasts along the entire Pacific Ocean. In South America, Peru and Ecuador bear the brunt of El Niño’s terrestrial wrath as the resulting storms bring influxes of water into the arid regions along both nations coast causing severe flooding and erosion.

The resulting flood waters destroy homes and crops while limiting transportation capabilities, further wreaking the Peruvian and Ecuadorian economies.

The eastern part of South America typically suffers similar adverse consequences of El Niño. This season, however, the Argentine and Paraguayan ministries of agriculture have released separate reports indicating that the humidity and lighter rainfall from the expected El Niño later this year will push their soybean yields to record heights at 55 million tons and 10 million tons respectively. Such harvests are expected to help both countries offset any infrastructural or transportation setbacks caused by El Niño.

While Argentina and Paraguay expect positive returns from the upcoming El Niño, the other two soy producing giants of South America, Brazil and Uruguay, are preparing for disaster. In Brazil, climatologists are expecting El Niño will increase cloud-cover and rainfall over Brazil’s ‘soy-basket,’ in the western portion of the country, while reducing temperatures. This combination will raise the probability of an outbreak of Asian fungus, colloquially known as ‘soybean rust.’ The fungus was the potential to spread out across the nation’s entire crop, potentially preventing Brazil from exporting its expected 90 million tons of soy this year. Uruguay is also expecting higher-than-normal rainfall, especially in its soy producing regions which would flood fields and cripple its capacity to produce soy.

The economic enfranchisement of Argentina and Paraguay over Brazil and Uruguay could have significant political consequences. All four of these nations are principal members of Mercosur, one of two dominant trade blocs in South America. Should Brazil and Uruguay’s trade capacities be impaired by El Niño, the more fortuitous nations will likely be forced to trade their products intraregionally rather than internationally.

Regardless of the possible ramifications, South America and the international aid community are dusting off their well-worn aid plans for when El Niño makes its presence known.