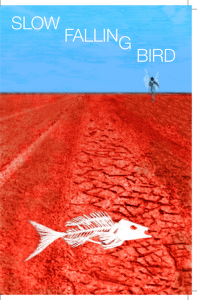

Theater Review: ‘Slow Falling Bird’

As part of the season Where We’re From: A season of Origins and Migrations, the Georgetown Theatre and Performance Studies program is currently showing ‘Slow Falling Bird’ by Christine Evans. The play is set in the writer’s homeland—Australia—and focuses on the plight of asylum seekers who arrive on the island’s shores by boat. Commonly known as ‘boat people’ and predominantly hailing from the Middle East and Northern Africa, this particular set of refugees is famously subject to extremely harsh living conditions in the detention centers they are mandated to live in upon arrival.

Through the stories of orphaned siblings Leyla and Mahmoud and new mother Zahrah, the play focuses on the brutality of life for the refugees in Australian detention centers, drawing on the barren landscape of the desert location as an allegory. The treatment of babies, the state of medical care, basic hygiene, force feeding and sexual assault: all core issues in the topical discourse were spotlighted within the show’s duration. The first scene featuring the asylum seeker characters opens with Leyla, a young orphan from the Middle East, attempting to clean her own and her brother’s faces by spitting on her dress and using the rag-like material to scrub away the visible grime etched into their skin. This simple gesture effectively emphasizes the incomprehensible severity of the detainee’s impoverishment by implying a dire lack of access to things as basic as soap and water. Water is a main theme throughout the play; in which it is used as a symbol for the fruits of life in general. Scenes of the Australian guards wasting water and consuming it carelessly are juxtaposed with depictions of thirst and struggling gasps for water from the refugees. This contrast represents the guard’s squandering of their advantages as Australian citizens, while the detainees risk their life and underwent daily tortures in order to gain any sort of legal status as a resident.

The storylines of the guards serve as a vehicle for explicitly making a connection between current Australian immigration issues and historical treatment of minorities in Australia. One of the guards, Micko, is an aboriginal Australian who talks of his upbringing in a missionary. This is a reference to Australia’s ‘Stolen Generation,’ possibly the most infamous episode in Australian history.Australian government agencies took young indigenous children, particularly those of mixed race from their families and communities and placed them in missionary schools in order to culturally assimilate them into white Australian society. This policy was the domestic adjunct to the ‘White Australia’ immigration regulations, which persisted until the 1970’s. The White Australia policy aimed at preserving a culturally and racially homogenous Australian society, by precluding non-white immigrants from entering the country. Although today Australia’s major cities are some of the most diverse metropolitan habitats worldwide, the old attitude associated with earlier immigration policies has resurfaced in reaction to the recent influx of Muslim migrants. The play draws parallels between today’s ruthless immigration restrictions against even genuine refugees and old exclusionary and assimilationist policies in a number of scenes, where the guards brutally demanded the refugees to speak English, assaulting them physically when they were unable to abide. In the heyday of White Australia, immigration officers were legally allowed to request potential migrants to speak and write in ANY European language, meaning that, if undesirable for racial or religious reasons, they could even block those who spoke English, from entering the country.

The fundamental aim of the torturous conditions under which the asylum seekers suffer is also addressed overtly, and is perhaps the most telling testament to the overriding Australian political mentality toward these refugees. While defending his cruel treatment of one of the detainees, one of the guards notes, ‘Well you don’t want them telling their family to follow them over here, do you?’ In this mouthful of words, the goal of the asylum seekers’ inhumane treatment is clear. Although Australians like to see themselves as ‘The Lucky Country,’ they also seem to want to keep this pot of gold very much to themselves. If foreign people caught in war see the island home as a beacon of hope, there is a fear that a new way of thinking, a new religion and an endless drain on our tax dollars could overrun the nation. When politicians are openly refusing to sell their house to Muslims because they are Muslims, it is not hard to ascertain a popular regression into 1940s mentality. Only then, the country had to change out of economic necessity: the population was not big enough to maintain a wealthy society. This need has dissipated, and in its place is the desperate need of the new immigrants. In the 50s, Australians called them ‘New Australians’ and encouraged them to play cricket and attend Anglican services. In the 70’s, they encouraged them to bring their culture into the rich melange that Australian cities were becoming. Now, Australia just says keep out. Although the current national anthem was only adopted in 1984, it seems its refrain ‘for those who come across the seas, we’ve boundless plains to share’ has never been less true in all the short history of an immigrant nation, led by an immigrant Prime Minister, that’s most consistent policy is hard-line anti-immigration.