Troubled Waters: The South China Sea after UNGA 2015

At the 70th U.N. General Assembly (UNGA) in New York, which concluded last Saturday, the U.N. and the Association of Southeastern Nations (ASEAN) “affirmed the importance of peaceful settlement of disputes, including in the South China Sea, through dialogue and in conformity with international law.” Meanwhile, Malaysia, a country which has been relatively less vocal in the South China Sea territorial disputes, has decided to establish a naval base on its South China Sea coast and establish a landing force, which may indicate a lack of faith in “dialogue” or “international law” in the resolution of the disputes. At the UNGA session, ASEAN Foreign Ministers, including Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) Secretary Albert del Rosario, met with U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and the session’s president Mogens Lykketoft to discuss the ongoing territorial dispute in the South China Sea. However, while there have been many efforts to establish diplomatic talks since the disputes surfaced in 2010, no concrete steps towards resolution have been taken. The parties have not budged on their claims and and recent actions taken by the countries involved have led to escalations in tensions.

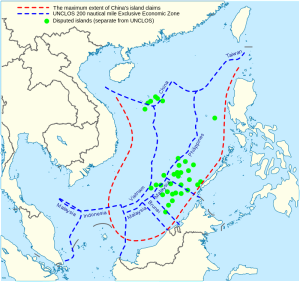

On March 30, 2014, the Philippines, supported by the U.S., filed a memorandum against China before the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea to contest China’s nine-dash line doctrine. During the UNGA session, the representative of China responded to a statement by the Philippines by saying that the Philippines’ invasion was the root cause of the island dispute in the South China Sea. He rejected the unilateral initiation of the arbitration process, stating that the issue should be resolved through bilateral negotiations based on history and international law. In addition to China and the Philippines, other claimants to the disputed Spratly Islands include Brunei, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Taiwan.

The seabed under the islands is believed to contain substantial undersea oil reserves. Furthermore, nearly half the crude oil and liquefied natural gas shipped around the globe travels through or near the South China Sea. As such, the impact of developments in these waters will likely be felt far beyond the immediate region.

The shift in Malaysia's stance could significantly alter ASEAN's relationship with China, the world’s second-largest economy. Currently, ASEAN member nations can be divided into three groups based on their attitude toward China. The first, consisting of the Philippines and Vietnam, takes a hardline stance, while the second group, comprising Cambodia and Laos, is pro-China. Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore and Thailand belong to the third group, whose sentiment toward Beijing is more or less neutral. However, if Malaysia starts to assume a more hawkish stance, as demonstrated by the recent announcement and the increased frequency of joint land exercises with the U.S., the regional balance could be upset.

The U.S.’s official position has always been for ASEAN and China to resolve the dispute between themselves. However, the Obama administration’s “pivot to Asia” strategy raises the question of whether U.S. will simply remain a bystander. In his speech to the General Assembly, President Obama stated, “the United States makes no claim on territory there. We don't adjudicate claims. But like every nation gathered here, we have an interest in upholding the basic principles of freedom of navigation and the free flow of commerce, and in resolving disputes through international law, not the law of force.” President Obama also advised that while “diplomacy is hard; that the outcomes are sometimes unsatisfying; that it's rarely politically popular,” it remains the only way to resolve disputes in the international order.

So how would ASEAN work together to resolve this dispute? Institutions in the Asia-Pacific are characterized by a commitment to musyawarah (consultation) and mufakat (consensus), that is, a process of “painstaking and lengthy discussion and consultation in which decisions emerge from the bottom up.” The institutional form taken by ASEAN was strictly intergovernmental and informal at its conception, vastly different from its western counterparts. Its founding document was a "multilateral declaration and not a treaty," and thus was not legally binding in any way. This emphasis on consensus in decision-making could paralyze ASEAN with regards to any concerted effort in the South China Sea issue. In 2012, ASEAN failed to produce a joint communique for the first time in 45 years due to disagreements over whether or not to include references to the South China Sea territorial disputes.

Two key agreements that may lay the foundation toward a peaceful negotiation of the dispute are the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) and the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea (COC). While the DOC was signed by ASEAN member nations and China in 2002, the more binding Code of Conduct has remained mired in inconclusivity due to China’s continued assertion of sovereignty over the disputed territories.

Is there possibility of resolution in the near future? The obstacles to the conclusion of the COC notwithstanding, both the DOC and the COC fail to outline specific measures towards peaceful resolution of conflicting territorial claims. The resolution of the disputes via international law also seems unlikely due to China’s unwavering resolution to participate only in bilateral negotiations, and the lack of any credible enforcement mechanism. Against this backdrop of stalled negotiations and China’s continued building in the South China Sea, one can expect the political status quo of the region to change as traditionally “neutral” states such as Malaysia work more closely with other claimant states to guard against Chinese assertiveness.