Water as a Soft Commodity

Later this month, the second piece of China’s South-North Water Diversion project is due to open. The new route will push 13 billion cubic meters of water more than 750 miles from the Danjiangkou dam in south of China to the capital, Beijing. The project aims to address water shortages in the north, which despite its size - compromises two-thirds of China’s farmland - has little fresh water yet. The south, contrary, holds about 80% of the country’s water resources. In recent years the disparity between the north and south has been exacerbated due to rapid urban growth and pollution of existing water supplies in the north. The severity of the issue prompted the Chinese government to launch the South-North Water Diversion project in 2002 despite the estimated $62 billion cost.

Later this month, the second piece of China’s South-North Water Diversion project is due to open. The new route will push 13 billion cubic meters of water more than 750 miles from the Danjiangkou dam in south of China to the capital, Beijing. The project aims to address water shortages in the north, which despite its size - compromises two-thirds of China’s farmland - has little fresh water yet. The south, contrary, holds about 80% of the country’s water resources. In recent years the disparity between the north and south has been exacerbated due to rapid urban growth and pollution of existing water supplies in the north. The severity of the issue prompted the Chinese government to launch the South-North Water Diversion project in 2002 despite the estimated $62 billion cost.

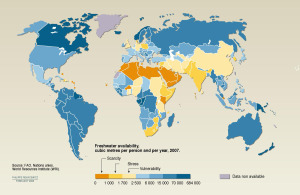

China does not face water scarcity alone; the issue impacts countries on every continent. The earth has sufficient freshwater for its 7 billion inhabitants. However, natural uneven distribution combined with affects of pollution and human wastefulness aggravates the issue. Around one-fifth of the world population faces water scarcity, and that number stands to increase because the rate of water use has exceeded the rate of population increase in the past century.

Climate change has also played a role in the water crisis. Last year the Potsdam Institute for Climate Change Research announced that climate change is likely to put 40% more people at risk of absolute water scarcity. In January of this year, new data from a pair of Nasa satellites showed that countries at northern latitudes and in the tropics are getting wetter, while countries at mid-latitude are becoming drier. In other words, wet regions are becoming wetter as dry regions become drier, effectively exasperating the existing issue of uneven distribution. The regions most at risk of increasing water shortages include the Middle East, north Africa and south Asia.

The growing prevalence of water scarcity has earned it a place as a global security concern. The 2014 National Intelligence Strategy of the United States released last month identified competition for natural resources, including water, as one of its national security priorities. Water scarcity translates into a security issue because of its potential to destabilize and increase regional tensions.

The idea of water scarcity leading to violent competition is far from fantasy; the relationship between India and Pakistan has the potential to become such a scenario. Pakistan’s agriculture-intensive economy relies on the Indus river system, over who’s upstream India has primary control. In 1960, the governments signed the Indus Water Treaty, which fixed and delimited the rights and obligations of each state concerning the use of waters. However, tensions have arisen in recent years as India began constructing new dams to address domestic water shortages and increase its hydroelectric power. Pakistan objected to the construction the Baglihar Dam in 2005 and the Kishanganga Dam in 2011 as violations of the Indus Water Treaty. In the end, both judgments favored India, although Pakistan gained limited rights to preserve its access to water. Tensions over water scarcity are likely to rise further due to Prime Minister Narenda Modi’s plan to construct more dams as part of a long-term project to connect 30 rivers.

Earlier this month, fighting broke out in the disputed region of Kashmir. The violence resulted in nine Pakistani and eight Indian deaths, violating a border truce that has largely held since 2003. The existing hostile climate, in combination with rising water resource tensions, could prompt an escalation of violence between the already antagonistic nations.

In Eastern Africa, “water wars” are not an issue of the future. In Ethiopia and Kenya, temperatures have risen about 2 °F since 1960, causing dry seasons grow longer. Tribes living in the area, particularly in the Omo-Turkana basin in northern Kenya and southern Ethiopia, depend heavily on the land to raise crops and nourish their livestock. Water scarcity has pushed communities to expand their range to search for water and arable land. As a result, competing tribes have resorted to killing, raiding livestock, and torching huts.

Besides local competition, tribes also face the imminent construction of two hydroelectric dams on the upper Omo River. The Ethiopian government plans to use the dams to meet its increasing energy demands. The dam will prevent the Omo River’s annual flood cycles, which supports an estimated 800,000 Ethiopian and Kenyan tribesmen. However, the Ethiopian government has denied claims that the dams will impact these communities. The situation threatens to increase refugee flows in the region, leading to tensions between Kenya, South Sudan and Ethiopia. In addition, the issue comes at a precarious time of oil field and pipeline development in East Africa. Therefore, tribal violence concerning water scarcity has implications for the future of stability between East African nations.

Water scarcity has become an issue worthy of international attention that necessitates regional cooperation and sharing of resources. Beyond widespread cooperation, experts support pricing and payment mechanisms that allow markets to improve management and reduce waste of water. Large-scale infrastructure projects may only provide temporary fixes, as in China, or threaten other’s access to water, as in Eastern Africa.