Special Report: When, Not If

when, not if

An exclusive interview

with Thai protesters

Arin Chinnasathian (SFS ‘22) is not too starry-eyed about his home country’s current prospects: “Everybody fears a coup and a potentially violent suppression. A coup is not far from reality.”

Since the summer, a Thai student-led movement has taken to the streets in Bangkok to protest against Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-o-cha. But Prayuth is more than just the prime minister; he is essentially a military dictator, having come into power after deposing the existing Thai government in a 2014 coup. While the former general has brought democratic institutions back into Thai politics, he and the military remain firmly perched on top. He has refused demands to resign.

The protesters have three seemingly simple demands: Prayuth’s resignation, an overhaul of the Thai constitution, and reforms to the role of the Thai monarchy.

Those demands have united the protesters, drawn from all sectors of Thai society. Yet, despite months of protests—in defiance of a state of “severe emergency,” coronavirus restrictions, and chemically laced water cannons—the Prime Minister does not look ready to budge. He has, however, promised to consider measures currently in the Parliament he controls.

The Caravel sat down with some Thai Georgetown students to talk about the unrest in their country. Two of them, Arin Chinnasathian (SFS ‘22) and Justin Potisit (COL ‘22), were willing to speak at length on the record. Two other students I spoke to, who decided to remain anonymous, made shorter statements.

Arin couched his statements in justifications historical and political; his statements betray a mind constantly searching for a right answer. Justin was more direct with his observations, quicker to express candid judgments and open frustrations when speaking.

Both had lots to say about their belief in democracy, their need for the world to pay attention, and their understanding of the power structures that prop up Prayuth and the military in Thailand. They even had some advice for Georgetown University.

Together, they steered the conversation towards the political dynamics that brought Thailand here, and towards the challenges the future will bring. What started as a history lesson became a master class in understanding authoritarian political systems, which turned into their stirring defense of the idea of a democracy of, by, and for the people.

For the U.S. citizens arguably facing their most consequential election in a generation, Thailand’s agitation for democracy should come as a warning: Arin and Justin expressed over and over again that real progress never happens overnight. But warnings are not prophecies. Thai protesters are determined to seize a democracy they believe is rightfully theirs, no matter how long it takes.

wikipedia.org/wiki/Thailand#Contemporary_history

Arin interrupted me almost immediately when I asked him to talk about how Prayuth seized power in 2014: “When you talk about the 2014 coup, people actually have to go all the way back and talk about the 2006 coup.” Justin cut in, “[for] which you have to go back to talk about the coups in the 70s.”

We did not end up talking about the 70s; Arin and Justin agreed that the 2006 coup was more important to today.

Thailand has a history of coups and coup attempts, but by 2006 the military had been out of politics for 15 years. In 2006, popular populist Prime Minister Thaksin was ousted after a year-long political crisis. The army usurped power “to protect the nation from chaos,” in Arin’s words.

Both of them struggled to remember what happened next. (Arin and Justin were both kids in 2006; how could they remember all the necessary details?) So, Arin pulled out the best resource he could find (“I’m opening Wikipedia up right now. Sorry, Advait, this is just…”) and shook his head apologetically.

The military rewrote the Thai constitution after being in power for a year, tweaking the Senate to lessen the strength of the existing political parties. After the first elections in 2007 brought a Thaksin-allied party to power, the Thai Constitutional Court dissolved that party—“the Constitutional Court just dissolves political parties. This is a thing,” said Justin—and the conservative Democratic Party took power.

In 2011, Thaksin’s sister, Yingluck, became the prime minister at the head of a new reform-minded populist party. But after her party proposed amnesty in 2013 for her exiled brother, anti-Thaksin groups protested, and she relented. Facing a political crisis over her actions, Yingluck dissolved Parliament and scheduled new elections, but the Constitutional Court stopped her—and then deposed her in 2014. More protests.

Here’s where Prayuth steps in. In Thai politics, the army has historically been the arbiter of political conflict. General Prayuth did in fact attempt to work with the two sides. But, in the end, he decided to arbitrate the conflict—“by staging a coup, of course, yes,” quipped Arin. In Thailand, that’s what arbitration means.

General Prayuth (red uniform, center left) marches behind Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra (white uniform, center right) during a parade in 2012. After a political crisis in 2014 challenged Yingluck’s power, Prayuth would lead a successful coup against her and install himself as the new Prime Minister. (Wikimedia Commons)

General Prayuth Chan-o-cha in a marching uniform. (Wikimedia Commons)

Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-o-cha during a 2016 meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin. (Wikimedia Commons)

“All the democratic process was suspended, the Parliament was suspended. Instead there was a national legislative assembly, all Prayuth-appointed, which functioned as the legislative body. And all the administration of the land was done by Prayuth-appointed people.

“In the past, when the military comes in, they usually will step down quickly, appoint a civilian leader to be PM, at least, in name. But, this time, they did not do that. So all political activity was frozen, and then the junta government drafted its own constitution, and then… Interestingly, they still use the democratic process of referendum to get a sense of legitimacy, but by trying to do that they control the referendum process. So the opposition couldn’t really voice their opposition to the Constitution. After the Constitution referendum was passed [in 2017] there are more changes to the Constitution done by the government. Gross violations of the democratic process there. But then after that, in 2018, the government called for an election.”

Yingluck’s party and the Democratic party returned to the public scene to challenge Prayuth’s military-led coalition. The media's attention, however, was fixated on their new competitor, the Future Forward Party.

Led by a charismatic businessman named Thanathorn, the Future Forward Party swept up young and disillusioned voters in droves. Arin voted for them; Thanatorn “was new in town, he was more committed to undoing the heritage of the military rule, as well as, most importantly, amending the constitution. His party was very vocal about it, as well as reforming the army to get the country out of a vicious cycle.”

The Future Forward Party exceeded expectations, achieving third place in the 2019 elections, behind Yingluck’s party and Prayuth’s party. Not only were those elections unfair, but in February 2020 the Thai Constitutional Court dissolved the darling Future Forward Party.

High schoolers and college students propelled the resultant protests, which began in February in reaction to Future Forward’s dissolution. The protests subsided due to COVID-19, but roared back to the forefront of Thai politics in June, after the reported abduction of a Thai dissident in front of his apartment in Cambodia. Since the summer, things have not calmed down.

Both Arin and Justin were unapologetic about giving me this whole story. They maintained that nobody can really understand Thai politics, especially not the current situation, without recognizing how Thailand got here—or without Wikipedia, I guess.

NO GOOD GUYS

It might be tempting to cheer for characters like Thaksin, Yingluck, and Thanatorn. But neither the reformers nor the reactionaries can really claim a moral high ground, according to Justin: “That’s the thing about Thai politics, there’s not really a [good guy].”

No good guy? Well, according to Justin, there exists a “cycle of [reformers] planning to reform corruption, then the people who are reformers are actually taking advantage of the reforms for their own good, and then those reforms getting struck down.” And then there's no reforms at all—“all the while it’s the people who are selling fried chicken on the side of the road who are being affected by this.”

Arin noted that “a lot of influential players in Thai politics are never really checked. Even Thaksin was able to infiltrate some of the checks and balances institutions.” So there’s some warranted skepticism of popular populists like Thaksin and Yingluck. But Arin maintains that “the [current] system is not less immune to corruption. It's more vulnerable to it than ever.” Reform that benefits the people is better than what they have today—which is why, to them, Prayuth is definitely the bad guy.

Arin spoke at length about how Thai politics remains firmly under Prayuth’s thumb, thanks to the current constitution, which “gives the power to Prayuth. Massively.”

It gives the Senate the chance to pick the Prime Minister. Because Prayuth and his military are the Senate, Prayuth has virtually indefinite executive power. And since any Thai laws must go through both the House of Representatives and the Senate, the opposition parties in the House must defer to his wishes: “if you don’t get the Senate on your side there will never be any progress in any of the reforms under the rules of the current Constitution,” explained Arin.

One quirk of Prayuth’s rule that no other major news outlet I’ve read has mentioned, but which Arin found to be of supreme importance, is the government’s creation of a 20-year National Strategy. Prayuth’s constitution mandates that the Senate must draft a set of goals that any government policy and that any elected government must adhere to. “And if they don’t follow they can be sued” by a government agency. “Anything related to that policy matter is hand-tied. That gives a way for the NCPO to exert influence over Thai politics over the next 20 years without even being in power. If this Constitution stays in place.”

These rules give “the military faction a latent influence in a way that has never existed before. Since 1997. There’s a real interest in protecting the current order.”

Protesters in Thailand push back against “the current order,” defying bans on gatherings and deftly evading police in order to better pressure the government to relent to their demands. (Wikimedia Commons)

Democratic mechanisms are “headed back, for sure, but a lot of it is still tied to the politics above the representative politics, which is the Senate and Prayuth’s network. So there’s no real independence.”

Arin decried how the government is using its powers to stall changes: ”Last month there were six motions [to amend the Constitution] on the floor of the Parliament—meaning the House of Representatives and the Senate—all have been delayed by the Senate move to create committees to study the proposal to amend the Constitution. The Senate still operates itself as a veto player.”

Arin, Justin, and their compatriots have had enough. “What the civil society and the current protesters are trying to do,” according to Arin, “is to advocate for a new constitutional drafting assembly, which is going to be elected in full using the country as one electoral district, all using the open list system. I think that’s the proposal right now. That one still has to go on to the Parliament floor. But that is part of the strategy, I think, on how any reform attempt could be done.” Arin later added: “And this is the only remaining safety valve to the current crisis, in my opinion.”

Lock up and crack down

A constitutional convention is the only “safety valve” because any other kind of transition, according to Arin, would more easily incite real violence. As mentioned above, that’s something both Arin and Justin fear. Prayuth apparently said that the current conditions were similar to those before he staged his 2014 coup.

“So far,” Arin explained, “suppression has come in the form of arrest and legal prosecutions and detention. But it has not manifested itself in the form of physical violence yet. But that has happened before, more than three times, most notably back in the 70s, twice. And then once in 1993, and very most recently against the Red Shirt protesters back in 2010.”

(Between our interview and this article’s publication, Arin let me know that “we're starting to see low-level physicality.” Recent headlines discuss how a Thai schoolgirl was slapped by a royalist for not standing up for the Thai national anthem. He also mentions “recent headlines of people throwing punches and objects at pro-democracy protesters.”)

So “they’re definitely [not averse to escalating]. And there’s a serious and coordinated attempt to paint protesters as violent and as someone who's threatening the freedom and lives of the monarchy institution. The protesters are calling for the reform of the monarchy, not to overthrow. Such [national security] excuses [have] been used against the protesters. Under that justification, the state of emergency was announced.”

Indeed, Prayuth imposed a “severe state of emergency” on Bangkok on October 15, but he revoked it on October 21. Apparently, according to officials, the "violent situation" had calmed down. (Thai protests have been almost entirely peaceful; meanwhile, Thai riot police in Bangkok fired water cannons laced with irritants at protesters.) Prayuth’s emergency decree only led to larger rallies.

Food hawkers on Bangkok’s streets are often better at reaching new protest locations than even the protesters themselves. After all, you can’t fight a government on an empty stomach. (Twitter)

Prayuth ignored protester demands to resign by October 24, though he did say that the crisis should be discussed in Parliament. On October 26 and 27, Parliament held a special session, but it did not really consider any protest demands.

Prayuth doesn’t seem to be backing down, but he probably knows that Thai citizens consider his government to be wholly illegitimate. Arin and his compatriots want Prayuth to resign and want the junta to reconsider the Constitution for good reason: “so there’ll be no legitimacy deficit that the current Constitution has, and [to] get rid of the power structures associated with it.”

If you can’t have a government you can trust to represent you, then who else can fight for you where it matters?

His majesty

Hint: not the king. For really the first time in a century, protesters are daring to question the Thai monarchy’s place in society. According to other journalistic accounts, Prime Minister Prayuth and King Maha Vajiralongkorn are in cahoots, centralizing their political power in ways that severely undermine any hopes for democratic rule in the current system.

While King Vajiralongkorn’s late father was beloved, Vajiralongkorn himself does not seem popular. Plagued by romantic scandal, and spending most of his time away from Thailand in an estate in Germany, the King has used Prayuth’s military junta to his advantage. He has taken ownership of government assets formerly held in trust for the Thai people, strengthened the military regiments loyal to him, and received huge paychecks from the Senate. On October 23, the King, in front of a crowd of supporters, publicly praised a man who faced off with protesters.

The German government decided that the Thai King was not yet violating any laws while living in Germany, but that he will be kept under investigation while he is there in the future. The King’s diplomatic immunity as a head of state might complicate that. (Twitter)

Prayuth and the military have cracked down to allegedly protect the King and his family. That’s not new, though. Former Thai military regimes have done the same.

And nobody can really say anything about it. In Thailand, you can be jailed for up to fifteen years for criticizing the royal family. Importantly, not one of the students I talked to made any comments about the Thai monarchy when I asked—that’s not a law any of them wanted to mess with, and for good reason.

Thai protesters have outsourced the task of criticizing the monarchy to friends in Hong Kong. Pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Thailand dub themselves the “Milk Tea Alliance,” and this is not the first time they have helped each other fight for their freedoms. (Twitter)

Well, almost. Two students gave me anonymous comments—not about the King, but about his yellow-shirted royalist supporters, who have lately been clashing with pro-democracy protesters in defense of the King.

The first comment concerned the royalists’ hypocrisy: “I find the logic of many royalists hard to comprehend. Their support is usually based on the perception of moral authority and diligence of the previous king. At the same time, they usually admit that that might not be the case anymore today. They then draw an immediate conclusion that the problem lies with a person, not the institution, and label any criticisms of the institution itself as libelous.”

The second urged royalists not to oppose protesters: “I have lots of friends who are royalists, who support the [monarchy]. I get what their concerns are. They’re concerned about corruption, they’re concerned about progress as decoupling Thai society from its heritage, but the demands of the protesters are very clear. At least the initial ones. Even if you believe in incrementalism, then you have to be open to at least [slower, less radical reforms].”

Nobody whom I talked to criticized the King, his family, or the idea of monarchy—they stuck to criticizing only the public institutions they saw as damaging their prospects for democracy.

Legitimacy Deficit Spending

One institution Arin and Justin highlighted as demanding change is the Thai military. Because every Thai male has to perform some military service (both Arin and Justin went through officer training last year), it would be hard for Thai citizens not to feel in touch with their military. They’re everywhere in society, even running the hospitals. (And they run the government now, too, if you hadn’t heard.)

Arin detailed the military’s role in society: “In the past, it has been a very relevant actor and an often-used actor when it comes to disaster relief, for example. So you frequently see the military engaging in activities which could eventually become political, and in activities where, if you’re in a democratic society, could be [taken on] by other institutions. In itself, that’s not bad, but it makes the responsible civilian authority seem irrelevant and incompetent.”

Justin pessimistically judged that “the only real way for us to move forward as a country is to put the military under civilian control. But that hasn’t happened yet. And it’s unlikely to happen in the near future. Change is hard. Institutional change is even harder.”

Despite Thai citizens’ proximity to the military, it is not really bursting with camaraderie. Arin described how lower-ranking officers are abused, especially conscripts; some have even died under conscription. “However, any attempts at investigation have been stifled. Any attempt to sue formally would be intimidated.” The military’s leaders keep their troops in line.

So, Arin continued, “this frozen structure makes it hard to be incentivized to change their situation. What do they lose? They lose their power. With their power, they know that they’ve been taking advantage of the system. They’re afraid that if they lose power, then the system will come back and bite them.”

It’s clearly dangerous for the military and police to send in men who could potentially sympathize with protesters. Defections are already happening. According to Arin, “there are officials in the army and the Royal Thai Police who have allegedly claimed that they resisted some of the orders from their commanding officers.”

Justin continued: “Two nights ago, there was a [policeman] who came up, he was like, ‘I saw the dispersal of the protesters and I can’t really stand with the military and the people who are doing this anymore. I’m putting myself out there. I know that this is wrong. So I’m not going to participate.’” That policeman is not alone.

Journalists covering Thailand’s protests have pointed out that the domestic conditions for repression of protesters are quite different. In Thailand, the police are far more sympathetic. (Twitter)

The police and military are pre-empting a general mutiny with a time-tested imperial tactic: “The police that they’re using are from random departments in the Thai police. They’re using the border police and the tourism police. Why wouldn’t they just use the regular police? This is why. They want to keep the integrity of their power structure intact,” said Justin.

The military is right to be worried. After the 2014 coup, for the first time in Thai history, the military junta neither transitioned the country back to a civilian leader nor left democratic politics. Prayuth’s junta has a whole lot more power thanks to those unprecedented moves, but they’ve arguably lost way more legitimacy in the process.

So the police and military have been doing what they can to threaten protesters and halt the movement against them. After all, if the protesters get their way, the military will certainly lose its place in civilian government.

To Arin and Justin, though, that’s no longer an “if.” It’s a “when.”

Who said idealism was naive?

The protesters demand three things: Prayuth must resign, the Constitution must be amended— or, hopefully, entirely rewritten—and the monarchy must be reformed.

The House tried working on that first demand on October 27. The opposition party called on Prayuth to resign; Prayuth shot back: “If there had been no coup back then [in 2014], would there have been rioting? Have you forgotten what you did then that caused the chaos and corruption? You seem to have a short memory.”

In the meantime, according to Nikkei, “The government's quarreling with the opposition overshadowed any effort to address issues raised by youth-led pro-democracy protesters.” The Parliament did not strike any compromise, not even to create a committee to investigate protester demands.

If the government won’t compromise, neither will the protesters. They’ll stay on the streets. And because they know that Prayuth knows that his rule is illegitimate, they’ve got a plan. Sort of.

The next elections are in two years and, this time, everybody knows they’re going to be a sham. Thanks to that fact, Arin believes that the government has an incentive to call for a new constitution, a democratic one, before those elections happen: Prayuth “has only two years left [before the next election]. So there’s a timeframe. Constitutional drafting, if it’s approved at all, will take another year at least. It is expected to be a protracted process. The whole thing could be about five years max.”

Justin was more cautious: “Much of the discourse in Thailand is predicated on ‘generational shock.’ I would say we have to wait until the current leaders are no longer alive in order for a new generation to come. I think we are in for the next fifteen years, at least.” But it would be a mistake to call that pessimism.

Rather, both of them know that no single overnight change is going to give them what they want. When it comes to a new democratic constitution, no amount of time is too long, “as long as,” says Arin, “discussions are done in good faith.” Small incremental progress would be better than sham elections with a sham government.

The conditions that motivate Pakistan’s protests are markedly different from those of Thailand, but their protesters have similar grievances against what they say is a government bought and run by the army. (Twitter)

The protesters have at least one thing going for them: they represent no political party. The original student movement has turned into a broader coalition transcending previous political splits. As long as their demands stay simple, they boycott what they see is a broken electoral process, and they continue avoiding the law with their evolving protest “language,” their pressure campaign cannot easily be co-opted.

Arin eloquently described the biggest lesson he’d learned so far: “‘Everyone is a leader’ is one of the many slogans of this movement, and I have come to recognize how true that is. Many supporters of the regime usually say they understand what youth is saying but asks youth to tone it down. I find that ironic. You can never negotiate if you don't come from a position of strength. And it's scary to speak truth to power alone, but if everyone comes together, it's less scary.”

The Thailand that Arin and Justin and their compatriots want to see can only be achieved when they work as one. To them, that’s not an unattainable ideal. Right now, it’s very real.

Thailand and the World — and Georgetown

“Why should citizens around the world care about what’s happening in Thailand?” I asked.

“It’s a human rights crisis?” Justin fired back, lilting his voice to hint that the answer should be obvious.

Arin was more diplomatic: “What goes on here might have repercussions for democracy movements or democracy agitations anywhere. If you are a supporter of democracy, this is where your attention should be right now, as it is a make or break movement for Thai democracy as well as any authoritarians and pro-democracy elements anywhere looking to formulate their next actions.” Indeed, new pro-democratic unrest inspired by the events in Thailand has risen in Laos, while Chinese state-run media disparages Thai protesters as pawns of the West.

Pro-democracy protesters elsewhere might say all the same things—but I doubt Arin and Justin think that not being unique is a bad thing, especially since all they want us to do is pay some attention.

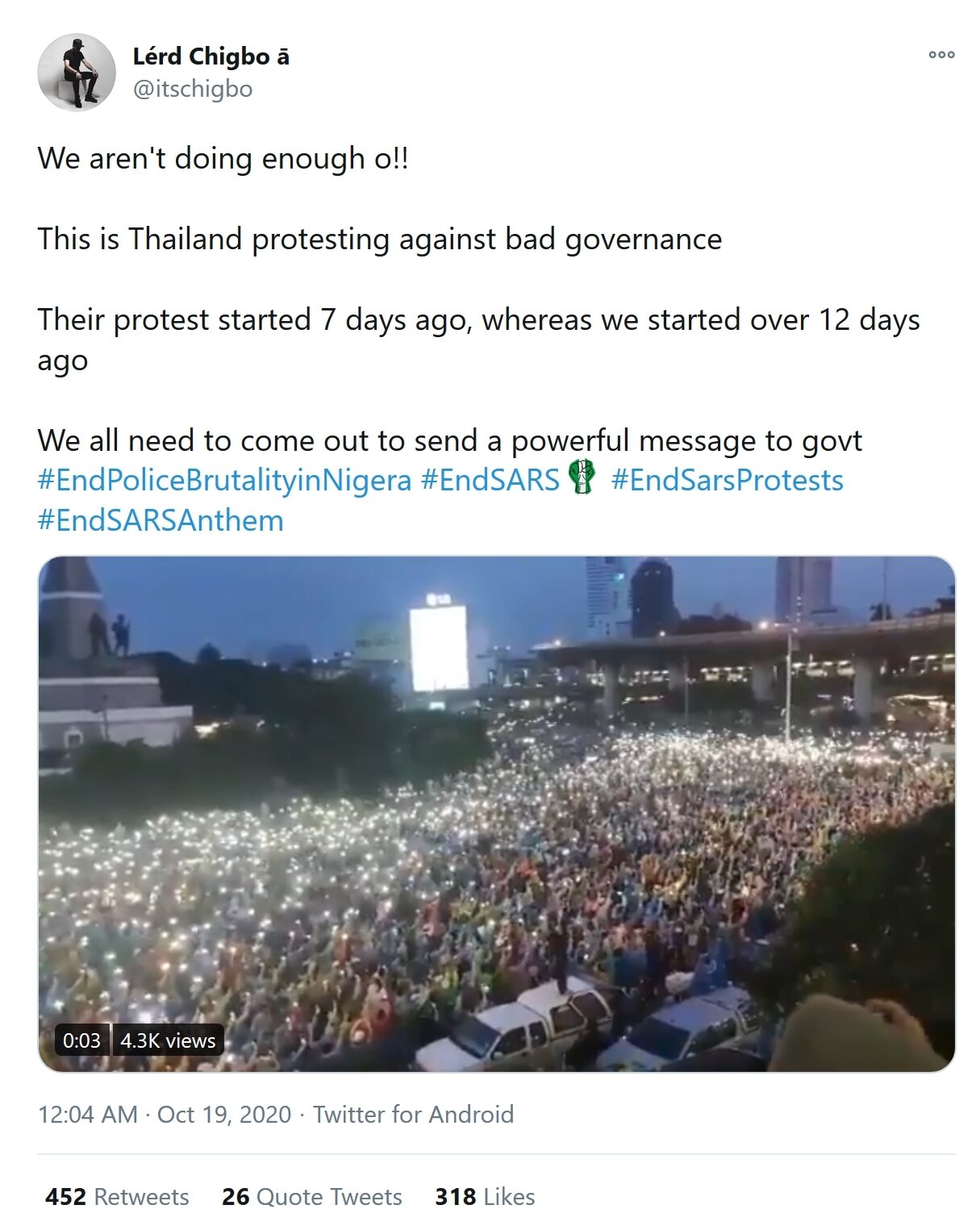

Protesters in Nigeria are exhorting their fellow citizens to be more like Thai protesters. Nigerian protesters initially were protesting against police brutality, but their protests have morphed into wide-ranging denunciations of their government, and have been met with increasing violence. (Twitter)

When I asked how they wanted people around the world to help them, Arin quickly let me know, “We’re not calling for foreign intervention, we would never want that.” He’s talking to a U.S. citizen, so I get it.

He continued: “But all we are hoping is that people from afar would at least help us spread the word if the government responds disproportionately against the protesters.” Arin said, multiple times, that the best thing concerned citizens can do is simply pay attention, and “find any means possible to pressure the Thai government not to use violence against the protesters. How do regular citizens do that? You guys could petition your own governments and write to them that they should help to monitor the situation.”

Implicit in that demand is the recognition that citizens around the world can only help one another across borders when they have governments that adequately represent their concerns.

But governments aren’t the only place through which Arin and Justin seek help. They also called on Georgetown University to do its part, positively rattling off requests.

“[Georgetown University President] DeGioia can put out a statement,” said Justin. Georgetown can “call on civil society organizations to help monitor,” said Arin. “Keep supporting GUThai,” Justin continued, referencing Georgetown’s Thai student organization. And the university must continue “upholding freedom of speech on campus. Making sure students will get the protection they need,” finished Arin.

All those demands sound quite realistic. To GUThai, they’re necessary.

Arin, Justin, and their fellow GUThai members have joined forces with students attending schools across 24 countries and territories protesting against Prayuth. Their “Coalition of Concerned Thai Students Abroad” dropped a comprehensive statement on social media on October 20. It has since been covered by Thai news outlets and, according to Justin, was even recognized by some Thai opposition figures.

The Coalition of Concerned Thai Students Abroad is now hosting events with Thai associations around different universities to educate anyone on the situation in Thailand. (Facebook)

All of which is to say that, if Georgetown University clamps down on political discourse, GUThai might not be able to use their organization to support their allies abroad and in Thailand. Arin and Justin see the University as a critical civil society organization, one they hope can be helpful.

Knowing You’re Right

Today, there is no shortage of literature on the alleged death of democracy and the challenge of authoritarianism. The jury—and the journalists—are still out on its causes. Still, it does not seem wrong to say that democracy fails when it does not deliver what it promises.

That view is bolstered by recent columns that describe the downsides of popular democracy, and hence why it might not deliver. Why do the people who are wrong get the same voice as people who are right? How do you overcome the inefficiency and instability of the masses? Don’t you just allow more people to be manipulated?

Authoritarians have used and continue to use those same questions to uphold their alternative, staid power structures. Prayuth, addressing the opposition in the Thai House, said on October 27: “Have you forgotten what you did then that caused the chaos and corruption? You seem to have a short memory.”

So how do Arin and Justin know that they’re right? Why are they fighting for what they’re fighting for?

Justin’s response was radio-friendly: “The fundamental demands of the protesters are kind of irrefutable. Don’t lock up people who disagree with you. It’s something that you learn in kindergarten. How could that be something that is incorrect?”

Arin took a more meandering, philosophical stance: “Precisely because I don’t know what is right—I don’t know what is the best direction for the governance of Thailand—I think that the democratic process is what I should uphold, personally. It is at least a system—I mean, it’s not perfect, if you look at America right now, for example—but at least it’s a process where opposition can be heard, where conflicts can be solved in a civil manner if all parties come to the table in good faith.”

Justin seems to see democracy as something with inherent values built into it. For example, not silencing your opponents. Arin, however, made no claims about whether or not democracy had inherent values. He only highlighted what he sees is the intrinsic value of democracy itself: effective governance by the people “is doable in a way that any form of autocracy or authoritarians cannot.”

Importantly for both Justin and Arin, democracy avoids political violence, whether that comes in the form of not jailing opponents or, in Arin’s words, by allowing “the opposition to creatively contribute towards finding ways to govern a nation without as much potential for violence as other forms of governance. I might not agree with everything the protesters have to say. But the democratic process and the parliamentary process are the only solution for all these demands to be discussed properly.”

These simple sentiments aren’t unique. Nonetheless, history proves them to be convincing. It’s not like Justin and Arin are the first to deploy this logic in service of their country.

However, they didn’t answer my question. Forget the value of democracy—how do they know they’re right to be out there protesting along with everyone else?

Justin’s answer juxtaposed his privilege and his proximity: “I know I’m right because I’m raised as someone who is listening to the grievances of people who are less fortunate than I am. Who are you going to listen to except for the people, in the end? I know that the situation in front of me can be ameliorated.”

Arin looked into his own story to find the answer: “I’m educated in Thai school. I grew up in a family of bureaucrats. I’m under the support of the Royal Thai Government to study in the United States. So it’d be very far from [the] truth to say that I am supporting this out of nowhere, because I am supporting this out of good faith to my country and for my own future.”

It would be hard to envision any social movement in the world without people like Justin, who believes that others’ struggles are worth his participation, and people like Arin, who just wants to take his country and his people in what he thinks is the right direction. Their motives are different, but they are hardly incompatible. Their shared demands are simple, and their resolve is strong.

When—not if—the protesters get their constitutional convention, they will surely celebrate. But they know better than anyone else how much work is left to do. Indeed, forming a new Thailand is a challenge wholly different from protesting against a government.

Successfully changing society is a scary idea. But the simple lesson that has propelled Arin this far will remain useful no matter what happens: “if everyone comes together, it's less scary.”